In the summer of 2017 I traveled in Hong Kong and Macau, and visited Shenzhen. During my time in Hong Kong I was able to use the internet, and relied on Google Maps to find street markets when I became lost. Of course I’d heard about the Great Firewall of China, which is also called the “Golden Shield Project” within the country. I hadn’t, however, quite realized how comprehensive it was until I checked into my hotel in Shenzhen and saw this card.

I apologize for the poor lighting in these images. I’ve taken pictures of both the front and back of the card. As you can see, the hotel explains that many websites are blocked and that “foreign VPN connections are unstable in China.” The latter is certainly true, as the Chinese government began a concerted effort to block all Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) about two weeks before I arrived in August 2017. A VPN is one of the best security tools that anyone can use on the internet. About two years ago my work Google Account was hacked. This meant that the hacker had access to not only my email, but also Google Docs, and all the work sites that contained my personal information. Ever since that time, I have used VPNs on public wifi (coffee shops, airports, etc.) to make it more difficult for a hacker to discover sensitive information. In Hong Kong my VPN worked without any difficulty. In Shenzhen, I did not even try, as such networks are completely unstable, if they function at all.

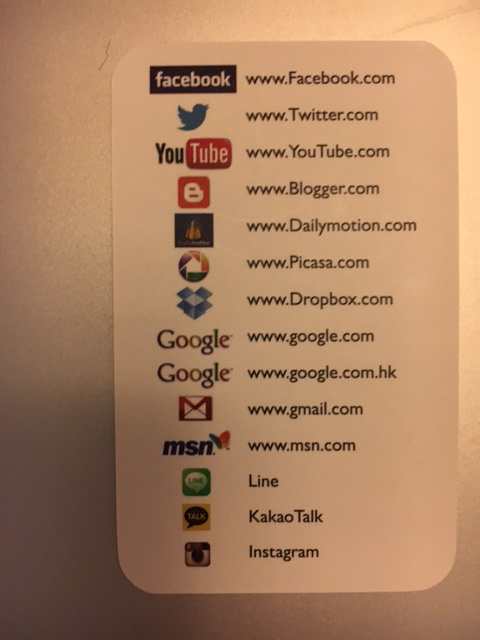

What was striking was the sheer length of the list of the websites and services that were blocked, as you can see from the reverse of the card in the picture at the bottom of this blog post. You can’t access or use Twitter, Facebook, Dropbox, Instagram, YouTube and of course Google. This doesn’t only mean that you can’t do searches using Google. It also means that you can’t use the entire Google suite of services, such as Google Docs, Sheets, Drive and Mail. Since this list briefly describes the core resources that I use for my work life, I wasn’t able to use my work email or resources while there. Somehow, though, I hadn’t thought about other sites that I’ve come to rely on, such as Google Maps on my phone. And this list is incomplete. Many key news websites were simply unavailable, so you couldn’t access them even by typing in their web address.

Of course it was interesting to spend some time exploring internet resources that were specifically designed for use in China, such as Bilibili (China’s answer to Youtube) and Baidu (a Chinese search engine). In general, I found that their English language resources were quite limited. Of course, I don’t think that this would necessarily matter to the local people. Everyone around me on the subway and the street was on their phones watching videos, texting and searching the web.

I loved China, which was culturally rich, architecturally fascinating, and endlessly innovative. I was disappointed with my own Mandarin level, but I love the language and plan to continue to study it for the long term. While the language is globally important, I study it because it’s beautiful. For anyone planning to do business in mainland China, though, I would recommend taking a careful look at this list of online resources that will be unavailable. Shenzhen is an immense and modern city of perhaps twelve million people, which is a manufacturing hub for every sort of electronics product available. So there are a wide array of businesses and opportunities. But for people who rely internet resources for their work life, it might be a challenge to continue an online business without access to key sites and apps to which you are accustomed. You would probably want to think carefully about what alternatives you might use. If you are curious to see which websites are blocked, you can test the service at this website.

All this said, China perceives that these choices are in its national interest, as otherwise foreign corporations could track all of its data. Of course, the Chinese state also has its plans for digital surveillance, which include its forthcoming “social credit” system. Still, China and other nations worry that Google, for example, owns Adsense which sells its data to online advertisers. What data is transferred and how is this regulated? Recent scandals -such as the Cambridge Analytica case with Facebook- have increased global concern about how data on social media can be used for political ends. Facebook owns the popular texting application WhatsApp. French President Macron called last week for stricter regulation of the internet. A recent New York Times article suggested (see reference below) that the internet was dividing into three, supervised by the United States, Europe and China. In the West, we are accustomed to thinking that the internet is universal. But this is not the case, as I saw on this trip.

That said, what I will most remember about the people during the entire trip to the region was how that they wouldn’t just tell me the directions when I asked for help finding an address, but would insist on walking me until I could see the place that I was trying to find. And how people in the subways would help me with my luggage, and make sure that I figured out the right line, even as I traveled all the way from Hong Kong to Shenzhen. 谢谢

Reference: New York Times Editorial Board. (October 15, 2018). There May Soon Be Three Internets. America’s Won’t Necessarily Be the Best. New York Times.