One aspect of conspiracy theories that most interests me is that they are enormously powerful, yet academics almost completely ignore them in their classrooms. If you look at most syllabi for theory classes (every one I’ve ever seen) in the social sciences you will find that they entirely omit conspiracy theories. At the same time, based on my personal experience, if you spend much time with academics you will hear frequent reference to conspiracy theories. It is true that some of these theories focus on the plans of the administration, which is often composed of their former colleagues. But academics also often use them to explain broader questions of politics and history during informal discussions. But you’ll almost never find conspiracy theories in syllabi, textbooks, classes or academic articles.

Conspiracy theories flourish in times when people are frightened and feel powerless, such as during a pandemic. That was certainly the case during the H1N1 pandemic in 2009, and in Latin America -particularly Brazil- during the start of the Zika epidemic. Whenever a society or a nation suffers from deep political polarization conspiracy theories also appear, which reflect the loss of trust in not only the government, but also other citizens. My colleague Leopoldo Rodriguez and I wrote an article about the death of an Argentine prosecutor in 2015, which examined the competing conspiracy theories about this event, which collectively blamed his death on a plethora of foreign actors.

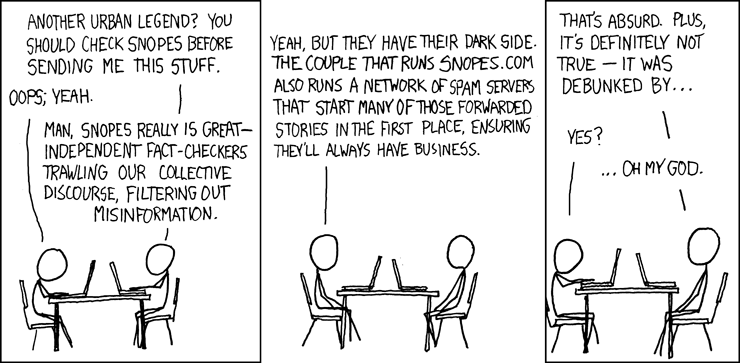

For all their importance and power, however, people are incredibly reluctant to discuss them in a serious manner. Part of the challenge is that when starts to study conspiracy theories one can travel down a rabbit hole that starts to make you doubt that you can trust what you know. Some conspiracy theories -such as those surrounding Jade Helm 15- are easy to dismiss. Others have disturbing elements of truth. For a better look at this issue, I strongly recommend the documentary by Charlie Lyne titled, “Personal Truth.” The filmmaker looks at the Pizzagate narrative in the United States, and compares these stories with those surrounding an alleged pedophilia ring -which likely never existed- in England. In both cases, these stories grew because of irresponsible actors, and because people want to believe stories that depict powerful people in a negative light. It’s also all too true that there are painful examples of evil behavior by people in power, which make these narratives believable.

What I most liked about the documentary is the manner in which the narrator questions his own beliefs, and even his own memory, during one particularly interesting moment in the documentary. His work does more than capture the power of these myths. He leads us to question how we really know what we know. At one point he discusses Locke’s work, An Essay on Human Understanding, to explain how the questions raised by conspiracy theories entail fundamental issues. The film is a personal, engaging and reflective look at why we believe what we do.

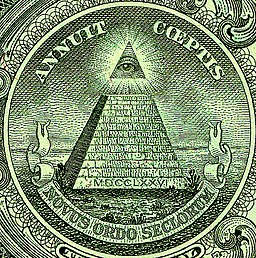

One challenge that anyone who does work with conspiracy theories will face is how do we change the minds of people who believe in conspiracy theories, such as the idea that Bill Gates and the Illuminati were behind the Zika epidemic? This was a very real belief, which I discussed in my own paper. In the end, as Lyne describes, when groups of people have faced powerful counter-evidence to their beliefs in the past, it seldom changed their minds. I still don’t have a satisfactory answer to this question, but what I do know is that argument and facts alone cannot change anyone’s opinion, even though it still important that these are available. I recommend watching Lyne’s work, which may leave you wondering whether you really trust your own stories that you use to define who you are.