Every Halloween I discuss an international mystery, or an aspect of folklore such as the ghost stories of southeastern China. This year will be different, because I am going to do three posts dealing with mysteries or the supernatural. With this post, I want to discuss the strange ship the Baltimore, a mystery with threads that reach from Ireland to Canada, and from the United States to Barbados. In his book, Maritime Mysteries: Haunting Tales of Atlantic Canada, Roland H. Sherwood tells the story (pp. 24-29) of how the ship mysteriously appeared in Chebogue, Nova Scotia. The local people wondered where the brigantine had come from, and why no people were seen on deck, even though someone had anchored the vessel. They sent ships, and people called out to those aboard, but no answer came. When local men boarded the ship on December 5, 1735 they saw signs of a struggle, including blood splattered all over the deck. There must have been a terrible battle aboard the ship. But of the crew there was not a trace. Seemingly, every single crew member had vanished. And everything valuable had been stripped from the ship. Then they heard the moaning within the cabin. They tried to open the door, but it had been barricaded shut. On that blood-soaked ship, they must have feared what they would find inside. When they burst through the door they found a woman on the floor, the only survivor. She said that her name was Susannah Buckler. Could she tell them what had happened to the ship’s crew?

A little digging on the internet soon revealed that the case had not only happened, but had left behind a rich historical record. The Calendar of State Papers, Colonial, from the period are online. On June 19, 1736 Armstrong wrote to describe his interview with the “one who calls herself Susannah Buckler. . . “ In his choice of words there is strong evidence that he doubted both her account and her identity. She told him that all but two of the eighteen sailors onboard had died during the voyage, and that when the ship washed ashore local Indians took the vessel. They carried her into the woods, and stole 1,600 pounds, a truly fabulous sum for the time. The Mi’kmaq also, she claimed, also took the boat’s merchandise. Again, Armstrong noted “. . . if her report be true. . . ” Armstrong also found it difficult to understand the deaths of her remaining crewmen: “From that circumstance of the boat, the two servants being afterwards found dead, as the two sailors are not to be found, we are not a little apprehensive of their being murdered.” Armstrong was both confused, while also being in the position of needing the woman’s account of events.

For this reason Armstrong sent along the woman’s deposition and began to make inquiries. According to Sherwood, they reached from the French governor in Louisbourg to the English governor in Boston. He reached out to the local Indians to recover the goods, and also sought to reclaim material from the boat that had been taken by a local man. His account ended with a denunciation of Romish priests and their influence in the area. If something was not done, “his Government will forever be insulted, and his British Subjects, if not murdered, robbed and molested.”

The online records also note the following resources, which were not digitized, and have not viewed: “Susannah Buckler’s (sic.) deposition; the Deposition of George Mitchell; Charles Dentremon, of Pobomcoup, Nova Scotia, upon the affair of the Baltimore, 11th May, 1736; Examination in Council of Peter Landry of Pobomcoup as to what he had seen and heard concerning the Indians and the Baltimore. 8th June, 1736.” Interestingly, the last two sources were translated from the French. After all, this was before the beginning of the expulsion of the Acadians from Nova Scotia in 1755. The tensions between English authority and a French Catholic population shaped Armstrong’s comments. Could there be any evil, in his mind, that was not linked to the Catholic priests in some way? In any case, there is a plethora of historical documentation concerning this event, which also includes the minutes of council of Nova Scotia, May 4th to June 7th, 1736. More copies of records may also be found in the Nova Scotia archives online index, which document that an alleged ship’s log survived.

The records also indicate that the local Indigenous peoples stated that when they found the ship all the people were dead, which contradicted the woman’s claims that there had been two other survivors. Instead, they stated that they had found eight people dead upon the shore, including a woman far along in pregnancy (2). So who had killed these people, if they did not die of disease, starvation or thirst? And why had only one woman survived? As for the ship, it apparently been destined for the Chesapeake Bay area of the United States, before its ultimate destination of Barbados.

Ironically, according to records from the time the mystery woman’s story unraveled when the real Susannah Buckler (Gwenda Morgan and Peter Rushton, 339) wrote to Armstrong searching for her husband (3). Sherwood states (pp. 28) that Armstrong told the council “She is not only an adventuress, but a splendid liar as well.” Sherwood also says (p. 29) that Armstrong never recovered the cargo ransacked from the ship. In the end, Armstrong seems to have sent the woman to New England before he uncovered the truth. Indeed, he wrote the Governor of Massachusetts that she was coming, according to one excellent academic study of this event (Gwenda Morgan and Peter Rushton, 339). One can only imagine his surprise when he learned the truth about Mrs. Buckler; for all his suspicions, it must have been a moment rather like the end (spoiler alert) of the film “The Usual Suspects.”

So what do we truly know? Despite Morgan and Rushton’s work many questions remain. Was Sherwood correct (p. 29) that Buckler had been one of the convicts aboard the ship, and if so is it possible to establish her identity? Some people have suggested that her true name was Mrs. Matthews, and that she had been a prostitute in Dublin, Ireland (Conlin, 76), based on newspaper reports from the time (4). Supposedly Matthews was famous for a fight with another woman who wanted to claim her dead husband’s body. According to a newspaper account, she had been arrested for theft (Gwenda Morgan and Peter Rushton, 340), which -if correct- probably explains why she had been sent to the colonies. There also is a record that she was referred to as “Dowdy” after she left Nova Scotia, so that also might have been her true name (Morgan and Rushton, 341). There is evidence that after leaving Nova Scotia she passed through Boston (Gwenda Morgan and Peter Rushton, 340). There she vanished, and with her the truth of what happened on that strange voyage.

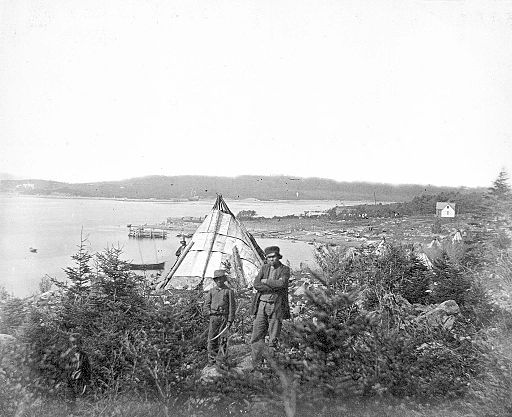

Nova Scotia is home to many historical riddles, such as Jerome of Sandy Cove, another mystery person found on the ocean’s edge. Such odd occurrences continue to take place in the Maritimes, such as 2010 rocket firing in the ocean off of Newfoundland. There are also many strange stories about the contemporary North Atlantic, so these mysteries are not confined to the distant past. Nova Scotia is justly famous for a its wonderful seafood and scenic beauty. But its always been a place rich in folklore and mystery, which is easy to forget when you are seeing the scenery at Peggy’s Cove, or eating the lobster at Ryer’s.

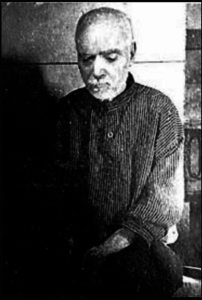

As for Lt. Governor Lawrence Armstrong, he seems to have led a tragic life. Just like the mysterious Mrs Matthews, his family also had an Irish background. After fighting in Europe, he was sent with Admiral Hovenden Walker’s expedition against Quebec. Walker’s expedition had been intended to seize Quebec from the French, but the campaign ended after navigation errors led many ships to wreck, a mistake that cost over 700 lives. Armstrong’s ship was amongst those lost. According to his record in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Armstrong was sent from Quebec to Annapolis Royal. After suffering a life of poverty, debt and privation, he rose to the rank of Lt. Governor. The position seems to have brought him little happiness, as he entered into endless conflicts with Governor Philipps. A sensitive man, he was humiliated by a merchant before his men who were drawn up on a parade ground, although it’s unknown when this event occurred (Murdoch, 529). One historian, Murdoch (p. 529) listed Armstrong’s failure with Buckler amongst the litany of Armstrong’s misfortunes before his death. He committed suicide at Annapolis Royal -the same place that he had arrived after the shipwreck, and from which he had worked to administer the colony- on December 6, 1739, four years after the ship the Baltimore was discovered. Unpopular and ill, he likely killed himself with his own sword, which his officers found lying beside him on his bed. It may have taken him some time to complete the act, because they found five bloody wounds on his chest. He had chosen to die almost four years to the day after that strange ship was first found.

One can only imagine the folklore that must have circulated around this event amongst the Acadian population. Perhaps these memories and folklore traveled south with them after their expulsion after 1755, a little over a decade after this ship was burned. Did versions of these stories get told in an old plantation on the Louisiana delta, while the mists wafted through the family cemetery out back? And what did the story tellers say about where the mystery woman escaped to?

It’s easy to imagine her taking on a new identity, and leaving the names of Matthews/Dowdy/Buckler behind. Ireland would have likely been too dangerous to return to, and it’s hard to see how she could have afforded a trip across the Atlantic. People at the time would sign themselves into indentured servitude for seven years to pay for the crossing. If she stayed in the colonies, it perhaps seems more likely that she traveled on foot from Boston. Perhaps she left for another colony, and wound up a barmaid in Virginia, or a farm servant in Maryland, where she lived a quiet life. Or did she marry a rich merchant, and found a respectable and wealthy dynasty? Or did she commit other crimes, for which she was punished under other names? Whatever the case, she seems to have taken her story -and how she managed to escape the authorities- to the grave.

According to one online source that I found she managed to escape to London before disappearing, which the best source on the topic also states (Morgan & Rushton, 340); another online source said that she had traveled to Annapolis, Maryland, but provides no evidence. One can imagine that her odds for vanishing successfully would have been greatest in a metropolis like London, where she perhaps could have returned to her old ways. Whatever the truth, she seems to have vanished from both authorities and the historical record so successfully that it seems unlikely that we will ever learn the truth. Still, the mystery woman is the most interesting part of the affair. Why did she pretend to be Susannah Buckler? Was she only trying to avoid being sent back to jail? Or was she perhaps trying to claim the value of the ship, after her supposed husband’s death?

I also wonder about the real Susannah Buckler too, whose husband Andrew Buckler died on that voyage. Her maiden name was Susannah Marshall. She had married her husband on May 23, 1720 in Dublin, when she was 24 years old. Did she ever learn more about what truly happened on that trip? According to one website that I found, Andrew Buckler -the captain of the Baltimore- was 41 when he died (born in Dublin, Ireland on November 3, 1694). He and Susannah had four children: John, Samuel, Stephen and Robert. In the end, Susannah Buckler had a long life and died in 1760, although the place of her death is unknown. I like to think that despite this tragedy, she and her husband now have descendants everywhere from Ireland to Barbados.

I have a couple of ideas about this story, and several questions. First, I wonder if there might have been another ship

involved in the events somehow. How else could all the goods have been taken away, unless the local people had seized them, as Armstrong believed? But somehow a large number of people also disappeared. And second, I wonder if the mystery woman didn’t have a friend in Boston. Is that why she wanted to go there? As skilled a liar as she proved to be, how else could she have vanished in an unfamiliar world unless she had some help? Perhaps there was an Irish household somewhere in Massachusetts where she knew that she would be welcomed, and her presence hidden. Of course, according to Morgan and Rushton (340) Governor Armstrong had himself given her a letter to a friend in Boston, whom he had asked to give her twenty pounds. So perhaps she didn’t need any other support.

In addition, I think that the eight dead people that the Mi’kmaq said that they are found on the shore are an important clue. It seems to me unlikely that these people were dead when they arrived on the ship. After all, someone could have easily disposed of them at sea. If so, the people most likely were murdered when they reached shore. I think that these were probably members of the ship’s crew (who else sailed the ship to anchorage?) and that more than one person must have killed them there. Did the mystery woman barricade herself into the cabin to protect herself from the killers? There may be other records that will reveal the truth, since I’ve only reviewed the documents that I could find online. There are still more records in the archives, perhaps even including the alleged ship’s log. So this blog post’s version of the story is incomplete, just as Sherwood’s earlier version was.

I’ve talked about this history with some family members who have a couple of thoughts of their own on this case. First, perhaps the mutiny took place only after the sailors had anchored the ship to take on water. So perhaps that was the one true thing that the mystery woman said. After all, it seems unlikely that the convicts have known how to furl the sails and set the anchor. If the crew let out the convicts from below decks to help move the water barrels or row the skiff to shore then the convicts might have seen the land, and known that this was their one chance to escape. Afterwards, perhaps they realized that they could not manage the sailing ship, so they tried to row away. If the inexperienced sailors tried to navigate coastal waters in the Bay of Fundy during a rising tide, that might explain the disappearance of many men. The tides in the Bay of Fundy are so huge as to seem to be unbelievable unless someone has seen them first hand.

I’ve talked about this history with some family members who have a couple of thoughts of their own on this case. First, perhaps the mutiny took place only after the sailors had anchored the ship to take on water. So perhaps that was the one true thing that the mystery woman said. After all, it seems unlikely that the convicts have known how to furl the sails and set the anchor. If the crew let out the convicts from below decks to help move the water barrels or row the skiff to shore then the convicts might have seen the land, and known that this was their one chance to escape. Afterwards, perhaps they realized that they could not manage the sailing ship, so they tried to row away. If the inexperienced sailors tried to navigate coastal waters in the Bay of Fundy during a rising tide, that might explain the disappearance of many men. The tides in the Bay of Fundy are so huge as to seem to be unbelievable unless someone has seen them first hand.

My family member’s second thought was that the mystery woman seems to have known enough about Susannah Buckler to have been able to emulate her rather well. Who could have told her so much about Susannah and their business except the captain himself? So they wondered if the two of them had formed a relationship before the uprising, which enabled her to learn a great deal of background information about this man, his wife, and his business. Of course, the woman might have learned all that she needed from a member of the crew. Still, it seems unlikely that she could have pulled off this charade convincingly without a great deal of information. The captain would have been the best source for this knowledge.

Lastly, there is the Wikipedia entry for Susannah Buckler. It says that some of the mutineers were tried in Salem, Massachusetts, although the link it gives to support this assertion is broken. The entry also doesn’t say whether the men were convicted. So perhaps buried in the judicial records from colonial Massachusetts there is an account of the true events in this story, or at least an alternative version that does not rely on the mystery woman’s word. After all, how could such a strange case not have a tie to Salem? And those records likely show how these men managed to leave the ghost ship. This story seems to me to be a wonderful topic for an graduate thesis, as well as a great subject for a film-maker. Armstrong’s interrogation of the mystery woman would make for a powerful narrative, with a shocking twist at the end.

There is, however, a song “The Ghost Ship Baltimore” by the Fighting Jamesons. The music itself seems a fusion, almost as if heavy metal met Irish folk, with a pounding beat, banjo and a fiddle. In this story, the ship set sell in the fall of ’47 (if this is 1847, it would have been during the Great Irish Famine), and there was no Susannah Buckler. Instead, an Irish man tried to escape to America in a ship with a crew of three, and met with tragedy. In this song -which was set more than a century after the real Baltimore’s arrival- the ship sank and the crew was lost.

Would you like to learn more about another Nova Scotian mystery? Read my review of Haunted Girl here, or Roland Sherwood’s wonderful book, which is filled with similar stories. I wish that I could have met Sherwood myself, and had the chance to talk to him about this mystery, preferably over some whiskey. You also can read my own book on a very old and evil spirit being in Algonquian belief: Dangerous Spirits: The Windigo in Myth and History. The book has its own accounts of the Chenoo, the Mi’kmaw name for the windigo, from narratives recorded in the 19th century in Nova Scotia. It also has its own stories of haunted waters (pp. 33-34, 53-54) but these are mostly not of the ocean, but rather the lakes and rivers of both Canada and the United States. If you do read it, please leave a review -good or bad- on Amazon or GoodReads.

Happy Halloween everyone, and if you are taking out children to trick or treat, please remember reflectors and glow sticks.

Footnote

- Sherwood also says (pp. 26) that the mystery woman appeared before the colony’s council on July 18, 1736. This date may be correct (I have not checked the council records for that date), but she had also clearly been already examined by Armstrong at least a month before.

2. Sherwood had access to sources that I have not seen. In his account (p. 29), however, the mystery woman was the only female among 59 male convicts. This information, however, seems to be contradicted by the Indigenous testimony to which Armstrong refers. In their account, a pregnant woman lay amongst the eight dead people that they found on the shore.

3. Morgan, Gwenda, and Peter Rushton. “Fraud and Freedom: Gender, Identity and Narratives of Deception among the Female Convicts in Colonial America.” Journal for Eighteenth‐Century Studies 34, no. 3 (2011): 335-355. This work is the only academic study of this case of which I am aware. Based on the newspaper account quoted in this article, Ms. Matthews -if that was the mystery woman’s true name- did not say that the Mi’kmaq had stormed the ship and slaughtered the crew. Indeed they appear to have cared for her well after taking her ashore, and made sure that she was brought to local Acadian settlers (p. 340). I am unaware of any evidence that they took valuables from the ship (apart from legal documents) although Armstrong seems to have believed this to be true, at least initially.

4. For a more recent summary of this case see the following work, pages 75-76. Conlin, Dan. Pirates of the Atlantic: robbery, murder and mayhem off the Canadian east coast. Formac Publishing Company Limited, 2009.

Murdoch, Beamish. A history of Nova-Scotia, or Acadie. Vol. 1. J. Barnes, 1865. For the unhappy events before Armstrong’s death see p. 529. For the letter to the Duke of Newcastle regarding the true events on the Baltimore see p. 518.

For one version of the story of the Carroll A. Deering, a ghost ship that foundered off of North Carolina, see the following: Whedbee, Charles Harry. Legends of the Outer Banks and Tar Heel Tidewater. Winston-Salem: John F. Blair. 1966. pp. 121-134.