In 2017 I spent some time in Hong Kong and Macau, and had the opportunity to speak to a number of academics. One of the most frequent questions that they asked me was whether people in the United States were following events in Hong Kong. I had to tell them no. There were so many major political debates taking place within the United States itself that events in Hong Kong hadn’t drawn much attention. That has changed now.

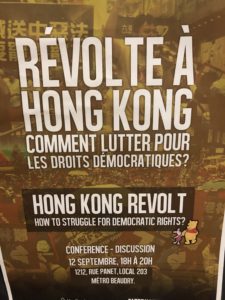

Britain returned Hong Kong to China in 1999, under a “one country, two systems” approach. In recent years, however, people have become increasingly concerned about their independence. For example, in 2015 five booksellers in Hong Kong went missing. At least one of the men later claimed that he had been kidnapped for selling books critical of China’s leadership. This context shaped how people in Hong Kong viewed a proposed law to allow the extradition of Hong Kong’s residents to mainland China. The bill was presented in April, and provoked massive protests by June. Even after Hong Kong’s governor withdrew the bill in September the protests continued to escalate. This issue has come to embody the fears of most people in Hong Kong that they will lose autonomy. For this reason, one of the protesters’ demand is for complete suffrage in the selection of their leaders, along with amnesty for those who have taken part in the protests, and an independent investigation of what they view as police brutality.

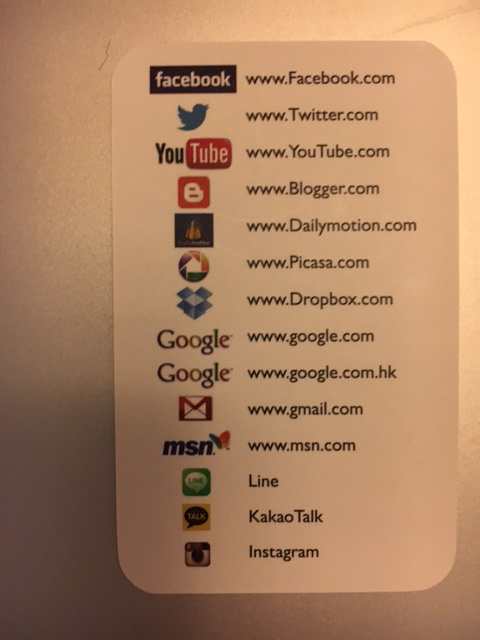

The opposition has adopted a process of mass collaboration, rather than identifying individual leaders. This makes it difficult for the government to shut down the protests by arresting particular people. It has also made social media absolutely central to the protests. In China, digital citizens live in an entirely separate internet environment. The Chinese government has long worried that Western corporations -Facebook, Google and Amazon- might enable espionage. Twitter and YouTube could also spread Western points of view on social and political issues. For this reason, the government created a parallel and different digital world. VPNs are banned in China. While there are some that may briefly work, the Chinese government is in a constant cat-and-mouse game to shut these down. For the most part, the Chinese state is effective at controlling them, so this is not an easy option to evade censorship or surveillance in China. But in Hong Kong people can use Twitter, WhatsApp, and many other similar services. As a result, the Chinese government has an interest in taking the political struggle to the digital realm in Hong Kong.

The Jamestown Foundation is a conservative think tank, which covers international affairs from a national security perspective. John Dotson had a recent article, Chinese Covert Social Media Propaganda and Disinformation Related to Hong Kong. The article describes how Twitter has suspended over 900 accounts based in the Peoples’ Republic of China (PRC). Facebook has taken similar steps, as has Google. Dotson points to five main themes in China’s social media campaign, which he describes in the following quote:

- “All Chinese persons, whether within or beyond the borders of the PRC, stand in unified support of Chinese government policies towards Hong Kong.

- The protest movement is secretly controlled by the United States—which seeks to bring about a “color revolution” (颜色革命, yanse geming) intended to overthrow the Hong Kong city administration, to separate Hong Kong from the rest of China, and to weaken China as a whole.

- The protestors are terrorists, equipped by the United States, who employ brutal violence and potentially lethal weapons against both police officers and the general public in Hong Kong.

- The Hong Kong police are courageous heroes protecting the public from violence and anarchy.

- The protestors are identified with various types of verminous insects.”

Of course it comes from a particular political perspective. But Dotson’s article is worth reading for an understanding how this struggle is taking place not only in the streets of Hong Kong, but also in the digital realm as well.

Another NPR article by Wood, McMinn and Feng revealed that China’s Twitter efforts to disrupt protest in Hong Kong had begun years before. Interestingly these Twitter accounts frequently posted pornography, presumably to attract views. A New York Times article found a similarly interesting list of articles on mysterious Twitter accounts: “Beginning last year, it retweeted news, most of it in English, about Roger Federer and the Premier League, and it shared juicy clickbait on Zsa Zsa, an English bulldog that won the 2018 World’s Ugliest Dog contest.” (Zhong, Myers and Wu, September 18, 2019). These accounts had often been stolen or purchased. China has been preparing these digital resources -including bots and accounts- for a long time.

What is particularly interesting is the allegation that the United States is covertly managing these protests, an allegation that has appeared in multiple other venues as well. Of course, the United States does not have the influence to create such a protest movement. This rhetoric, however, distracts from the political grievances driving the dispute.

China’s cyber reach not only allow the country to disrupt coverage of the protests, but also to conceal it on some platforms. Tik Tok is a very popular app that allows people to make short videos, including karaoke style music videos. It is also owned by a China-based company. As Drew Harwell and Tony Romm (2019) described in a recent article, the Hong Kong protests are virtually absent from Tik Tok. China’s digital prominence allows it to extend its censorship to entire platforms.

From a Chinese perspective, the Hong Kong protests are deeply challenging. They come in the context of a trade war with the United States which is encouraging multinationals to move production to Vietnam and other southeast Asian countries (for more on U.S.-Chinese relations please Campbell and Sullivan’s article in the references below). The protests make the likelihood that Taiwan’s citizenry would volunteer to accept Chinese rule -under the same “one country, two systems formula as Hong Kong- fade into nothing. And they come at a time when China’s relations with its neighbors -in particular Vietnam- are under strain because of China’s claims to vast swaths of maritime territory in the South Chinese sea. China has been trying to enforce its claims through a rapid maritime buildup, the dispatch of ships to contested waters, challenges to ships moving through the waters it claims, and the construction of artificial islands. Russia is upset that China apparently stole a Russian design for the J-15 fighter aircraft. Multiple Western countries are worried about that the Chinese telecommunications company Huawei (Mandarin 华为) might enable espionage if it were to be involved in developing their countries’ 5G networks. At this time of international tensions on multiple fronts the protests in Hong Kong are both challenging for China to accept, but also exceptionally expensive to confront with Chinese force. For this reason, trying to disrupt the protests by cyber means may be a more attractive option for the Chinese state.

Of course, cyber steps and digital surveillance also come with costs. Recent revelations about possible Chinese digital espionage in Australia are causing debate in that country (Packham, 2019). As China’s offensive cyber capabilities have grown, there has been concern about its cyber tools, such as its so-called “Great Cannon” (see Marczak et al., 2015). Of course such concerns elide both the vast reach and questionable morality the NSA’s cyber exploits. For more on this topic, I strongly recommend reading Scott Horton’s Lords of Secrecy. But it also ignores the reality that the majority of China’s cyber investments have been made in domestic surveillance, particularly against the Uighur minority (Samuel, 2018). China’s social credit system, however, applies mass surveillance to the entire population (Botsman, 2017). Participation in the system will be mandatory in 2020. For more on this topic I recommend Chen and Cheung’s study, “The Transparent Self under Big Data Profiling: Privacy and Chinese Legislation on the Social Credit System.” In this sense, cyber surveillance or social media campaigns against Hong Kong are part of China’s larger political project for the state.

It is also important to remember, though, that such policies are not unique to China. As the New York Times has described, cyber surveillance has shown up regarding the strangest of issues, such as a soda tax in Mexico. Nor is China necessarily the most worrying state for cyber espionage and warfare and Asia. North Korea -small, isolated and impoverished- has an impressive cyber force. Although many people might have thought that North Korea’s cyber forces were minimal, they proved their capabilities after the 2012 hack of Sony, which had released a film “The Interview” mocking North Korea’s leader. North Korea was almost certainly behind the Wannacry attack as well. The irony is that smaller nations that rely less on digital commerce may be less vulnerable to cyber attacks, and therefore more prone to use them. There is currently a cyber arms race in place, and China is only one of many nations in the race. Still, China has made massive investments because it views its cyberwar capabilities as one way to level the playing field with the United States, particularly given the U.S. reliance on digital networks and satellites, particularly for military affairs (Gompert & Libicki, 2014).

It is also important to note that China’s traditional espionage activities have also exacerbated relationships with other nations. One can see this for example with Canada. As Hsu described in a recent (September 17, 2019) article, China used a Canadian businessman to obtain data on a U.S. submarine rescue vehicle. The man and his firm both have plead guilty. Perhaps more serious were the leadership changes at Canada’s National Microbiology lab after it “shipped Ebola and Henipah viruses to Beijing on March 31, raising suspicions from experts in biochemical warfare, who say they think China may use the pathogens to develop offensive biological weapons.” (Lanese, 2019). After the shipments, virologist Xiangguo Chiu, “her colleague and husband Keding Cheng, and a number of her international students lost security clearance to their lab on July 5” (Lanese, 2019). Experts in the field raised many questions about why this transfer of extremely dangerous viruses took place (Blackwell, 2019). Of course, medical espionage involving China is not unique. In July two people (Yu Zhou and Li Chen) who worked at Ohio’s Nationwide Children’s hospital were arrested for stealing medical secrets after an investigation by FBI counter-intelligence, as Thomas Brewster (2019). described in an article in Forbes. The FBI apparently believes that these employees were stealing information on exosomes for China. Still, the Canadian case -involving the transfer of biosecurity level 4 viruses- is more serious. .

Cyber tensions are exacerbating all of these issues between Canada and China. In December 2018 Canada arrested Meng Wanzhou, a Chinese Huawei executive (CFO). Afterwards two Canadians were arrested for espionage in China, and China blocked key Canadian agricultural imports. Canada’s Prime Minister recently spoke about Canadian-Chinese tensions related to these arrests. While traditional espionage is causing international relations difficulties for China, all these questions are exacerbated by the questions that surround cyber espionage and surveillance. While Canada is only one country, similar narratives could be told for many other nations, such as Australia, in which concerns about cyber espionage is worsening relations with China.

While this started as a blog post on China’s use of cyber tools in Hong Kong, it’s also worth noting that China and the United States share many common interests in cyber security. While it’s easy to focus on their conflicts, in the larger picture they share a common goal of fighting cyber crime. Whether diplomacy can work in this issue is uncertain, but these two great powers do have commonalities. Of all these the most important is that both nations rely heavily on e-commerce and digital records. What would happen if an outside power hacked China’s surveillance network? The same tools that China has created to monitor its own citizens would create an unparalleled espionage opportunity not only for another country, but also for a non-state actor. Think of the revelations that came with the Panama papers scandal. What might a hack of Chinese systems reveal about the behavior of key individuals? It would make the books once sold in Causeway Bay book store in Hong Kong look trivial. The United States has created a similarly pervasive intelligence system. When a first day (previously unused) exploit was stolen from the NSA it led to devastating cyber attacks (Perlroth and Shane, 2019), including in the United States. So the exploit (External Blue) that led to billions of dollars in losses globally was developed with U.S. taxpayer funds, as Perlroth and Shane (2019) describe. For both China and the United States, tacit agreements and boundaries surrounding cyber espionage would provide benefits.

In the end, digital surveillance has not slowed the protests in Hong Kong. Instead, surveillance cameras are destroyed, and protesters carry umbrellas to protect themselves from facial recognition software. These steps are mostly low tech. A group of musicians recently met to record an anthem “Glory to Hong Kong” but the 150 musicians were afraid of being identified, and wore masks. Still, the protests continue, even after the Hong Kong government withdrew the extradition bill. And the protesters have proved adapt at using digital communications for mass mobilization and media communication. What has most struck me about the protests in Hong Kong has been their endurance. And if one follows some of the Hong Kong protestors on Twitter, one has to be impressed by their digital savvy.

It’s also worth remembering the sad fact that cyber tactics and political intimidation works in two directions. In an excellent CNN article, Caitlin Hu (2019) talks about how the protesters live in fear of facial recognition software. This fear can have terrible consequences. She describes how an elderly man taking pictures of protesters in Hong Kong was shoved to his knees by the crowd. People feared that he was a spy. He was forced to delete his pictures. And the police have a different take on cyber intimidation: “Senior police officials, speaking on condition of anonymity, said officers’ personal data, contact information, home addresses and more had been shared online, and described being doxxed as a form of `psychological war'” (2019). They have reasons for their fears: ” On encrypted app Telegram, channels dedicated to exposing personal information of people on both sides of the protest front lines have attracted tens of thousands of users..” And these pressures are also extended to the people installing the “smart posts” that people fear may contain surveillance tools: “Shortly after the lamp post fell, a government contractor supplying Bluetooth beacons for the posts abruptly withdrew from the project, citing concern about attempts to intimidate employees’ families” (Hu, 2019). What is striking from this account is not only the fear that both sides experience, but also the extent to which both sides perceive the other to be threatening them outside the law. The social costs for Hong Kong are very high if this political standoff continues without a negotiated settlement. Saša Petricic has a wonderful article in Canada’s National Post newspaper that details the impact within families when younger people protest, and the parents oppose dissent.

If you are curious to learn more about cyber issues I highly recommend the website of the International Cyber Policy Center at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI). The best way to track their work and what they’re following? Search Twitter for ASPI Cyber Policy of course. For an edited volume on China’s cyber involvement you might look at Cheung, Ming, & Reveron, China and Cybersecurity : Espionage, Strategy, and Politics in the Digital Domain by Oxford University Press. The first chapter by Nigel Inkster gives a good overview of China’s intelligence agencies, which play a key role in cyber espionage and warfare. Lastly, if you are really interested in the topic, I’ll be teaching an online class on Cyberwar and Espionage (INTL 366U) again this winter quarter at Portland State University, as well as an online class on digital globalization this fall. I’ll hope to see you there.

Selected References

Blackwell, T. (August 8, 2019). Bio-warfare experts question why Canada was sending lethal viruses to China. National Post. Retrieved on September 17, 2019 from https://nationalpost.com/health/bio-warfare-experts-question-why-canada-was-sending-lethal-viruses-to-china

Botsman, R. (October 21, 2017). Big data meets Big Brother as China moves to rate its citizens. Wired. uk. Retrieved on September 15, 2019 from http://teomeuk.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/05/Wired_Big_data_meets_Big_Brother_as_China_moves_to_rate_its_citizens.pdf

Brewster, T (September 16, 2019). Exclusive: The FBI Hunts Chinese Spies At An Elite American Children’s Hospital. Forbes. Retrieved on September 17, 2019 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/thomasbrewster/2019/09/16/exclusive-fbi-hunts-chinese-spies-in-american-hospitals/#5f1ccaf320f8

Burgess, C. (September 15, 2019). Canada Arrests Chinese Spy After Being Tipped Off by U.S. Intelligence. Clearance Jobs. Retrieved on September 16, 2019 from https://news.clearancejobs.com/2019/09/15/canada-arrests-chinese-spy-after-being-tipped-off-by-u-s-intelligence/

Campbell, K., & Sullivan, J. (2019). Competition Without Catastrophe: How America Can Both Challenge and Coexist With China. Foreign Affairs, 98(5), 96-110.

Cave, C. (November 29, 2018). The great wall of silence: Australia’s failure to talk about China. The Strategist. Retrieved online on September 17, 2019 from https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/the-great-wall-of-silence-australias-failure-to-talk-about-china/

Cecco, L. (September 16, 2019). Canada: arrest of ex-head of intelligence shocks experts and alarms allies. The Guardian website. Retrieved on September 17, 2019 from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/sep/16/concern-mounts-after-canadas-ex-head-of-intelligence-accused-of-leaking

Chen, Y., & Cheung, A. S. (2017). The transparent self under big data profiling: privacy and Chinese legislation on the social credit system. Retrieved on September 16, 2019 from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/84930493.pdf

Chung, K. (September 18, 2019). Black Blorchestra’ crew behind music video of protest anthem ‘Glory to Hong Kong’ voice fears about being identified. South China Morning Post website. Retrieved on September 21, 2019 from https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3027744/black-blorchestra-crew-behind-music-video-protest-anthem

Denton, J. (September 9, 2019). Chinese Covert Social Media Propaganda and Disinformation Related to Hong Kong. Jamestown Foundation Website. Retrieved on September 15, 2019 from https://jamestown.org/program/chinese-covert-social-media-propaganda-and-disinformation-related-to-hong-kong/

Gompert, D., & Libicki, M. (2014). Cyber Warfare and Sino-American Crisis Instability. Survival, 56(4), 7-22.

Harwell, D & Romm, T. Don’t look for the Hong Kong protests on TikTok. You won’t find them. South China Morning Post. Retrieved on September 17, 2019 from https://www.smh.com.au/world/asia/don-t-look-for-the-hong-kong-protests-on-tiktok-you-won-t-find-them-on-platform-20190917-p52s08.html

Horton, S. (2015). Lords of secrecy : The national security elite and America’s stealth warfare. New York: Nation Books.

Hsu, S. (September 17, 2019). Canadian businessman, his firm plead guilty to transferring U.S. Navy submarine rescue data to China, National Post (Canada) Retrieved on September 17 from https://nationalpost.com/news/world/canadian-his-firm-plead-guilty-to-transferring-u-s-navy-rescue-sub-data-to-china

Hu, C. (September 12, 2019). What Hong Kong’s masked protesters fear. CNN news. Retrieved on September 17, 2019 from https://www.cnn.com/2019/09/09/asia/smart-lamp-hong-kong-hnk-intl/index.html

Lanese, N. (August 9, 2019). Questions Surround Canadian Shipment of Deadly Viruses to China.

The Scientist. Retrieved on September 17 from https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/questions-surround-canadian-shipment-of-deadly-viruses-to-china-66254

Lindsay, J., Cheung, Tai Ming, & Reveron, Derek S. (2015). China and Cybersecurity : Espionage, Strategy, and Politics in the Digital Domain. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Marczak, B., Weaver, N., Dalek, J., Ensafi, R., Fifield, D., McKune, S., … & Paxson, V. (2015). China’s great cannon. Citizen Lab, 10. Retrieved on September 16, 2019 from https://citizenlab.ca/2015/04/chinas-great-cannon/

Packham, C. September 15, 2019. Australia concluded China was behind hack on parliament, political parties – sources. Reuters. Retrieved on September 16 from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-australia-china-cyber-exclusive-idUSKBN1W00VF

Perlroth, N. (2017, February). Spyware’s Odd Targets: Backers of Mexico’s Soda Tax. The New York Times. Retrieved on September 16, 2019 from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/11/technology/hack-mexico-soda-tax-advocates.html

Perloth, N & Shane, S. (May 25, 2019). In Baltimore and Beyond, a Stolen N.S.A. Tool Wreaks Havoc. New York Times. Retrieved on September 17, 2016 from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/25/us/nsa-hacking-tool-baltimore.html

Petricic, S. September 21, 2019. Hong Kong’s deep divide: Months of protests take their toll on families. National Post. Retrieved on September 21, 2019 from https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/hong-kong-s-deep-divide-months-of-protests-take-their-toll-on-families-1.5291971

Samuel, S. (August 16, 2018), China Is Going to Outrageous Lengths to Surveil Its Own Citizens. Atlantic. Retrieved on September 16, 2019 from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/08/china-surveillance-technology-muslims/567443/

Smallman, S. (November 26, 2018). The Great Firewall of China. Blog post. Retrieved on September 16, 2019 from https://www.introtoglobalstudies.com/2018/11/the-great-firewall-of-china/

Staff, September 5, 2019. Canada: Trudeau accuses China of using ‘arbitrary detentions’ for political ends. The Guardian website. Retrieved on September 17, 2019 from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/sep/05/justin-trudeau-china-canada-beijing

Wood, D., McMinn, S., & Feng, E. (September 17, 2019). China Used Twitter To Disrupt Hong Kong Protests, But Efforts Began Years Earlier. National Public Radio. Retrieved on September 21, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/09/17/758146019/china-used-twitter-to-disrupt-hong-kong-protests-but-efforts-began-years-earlier

Zhong, R., Myers, S.L., & Wu, J. (September 18, 2019). How China Unleashed Twitter Trolls to Discredit Hong Kong’s Protesters. Retrieved on September 21, 2019 from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/09/18/world/asia/hk-twitter.html