China, Hong Kong and cyber espionage

In 2017 I spent some time in Hong Kong and Macau, and had the opportunity to speak to a number of academics. One of the most frequent questions that they asked me was whether people in the United States were following events in Hong Kong. I had to tell them no. There were so many major political debates taking place within the United States itself that events in Hong Kong hadn’t drawn much attention. That has changed now.

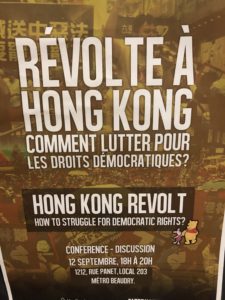

Britain returned Hong Kong to China in 1999, under a “one country, two systems” approach. In recent years, however, people have become increasingly concerned about their independence. For example, in 2015 five booksellers in Hong Kong went missing. At least one of the men later claimed that he had been kidnapped for selling books critical of China’s leadership. This context shaped how people in Hong Kong viewed a proposed law to allow the extradition of Hong Kong’s residents to mainland China. The bill was presented in April, and provoked massive protests by June. Even after Hong Kong’s governor withdrew the bill in September the protests continued to escalate. This issue has come to embody the fears of most people in Hong Kong that they will lose autonomy. For this reason, one of the protesters’ demand is for complete suffrage in the selection of their leaders, along with amnesty for those who have taken part in the protests, and an independent investigation of what they view as police brutality. …