Nukemap

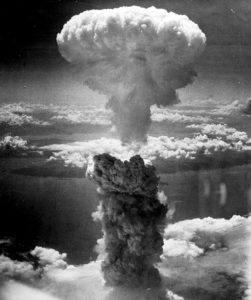

Nukemap is a website that allows you detonate a virtual atomic weapon over the city of your choice. You can select the size of the bomb either by kiloton, or by presets. I first chose the a nuclear weapon tested by North Korea in 2013, and tested it as a surface burst over my much-loved city of Portland. The results were horrific: an estimated 32,230 fatalities and 41,500 injuries. When I tested the same blast over Manhattan there were 103,000 fatalities and 213, 430 injuries. In each case the map generates a series of concentric circles that illustrated the impacts from radiation, fireball, air blast, thermal radiation, etc. The website also models the radiation plume, which trails far off into the distance on the map.

This website can take you to a very dark place. I made the mistake of modeling the largest bomb that the USSR ever tested, and what would happen if it detonated over Portland, Oregon. The largest circle was for the thermal radiation, and indicated the areas in which people would receive third degree burns. This circle stretched for 60 kilometers or 11,300 km2. One end of circle passed Yale, Washington in the north, while Silverton, Oregon was on the the south edge of the circle. For this particular example, there were 1,241,130 estimated fatalities, and 574,390 injuries. So people were much more likely to be killed than injured. When I then tested the same blast over New York City, the same blast caused 7,633,390 fatalities and 4,194,990 injuries. At that point I stopped using the site.

This website is both bleak and fascinating, and might be a useful tool during a classroom discussion of nuclear proliferation, and the development of North Korea’s nuclear weapons capability. The day that I visited the website in November 2017 over 130 million detonations already had taken place on the site.

Shawn Smallman, 2017

![By Cannabis Training University (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.introtoglobalstudies.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/512px-Cannabis_Plant-200x300.jpg)