Censored: China and its Digital Secrets

Roberts, Margaret E., Censored: Distraction and Diversion Inside China’s Great Firewall. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020.

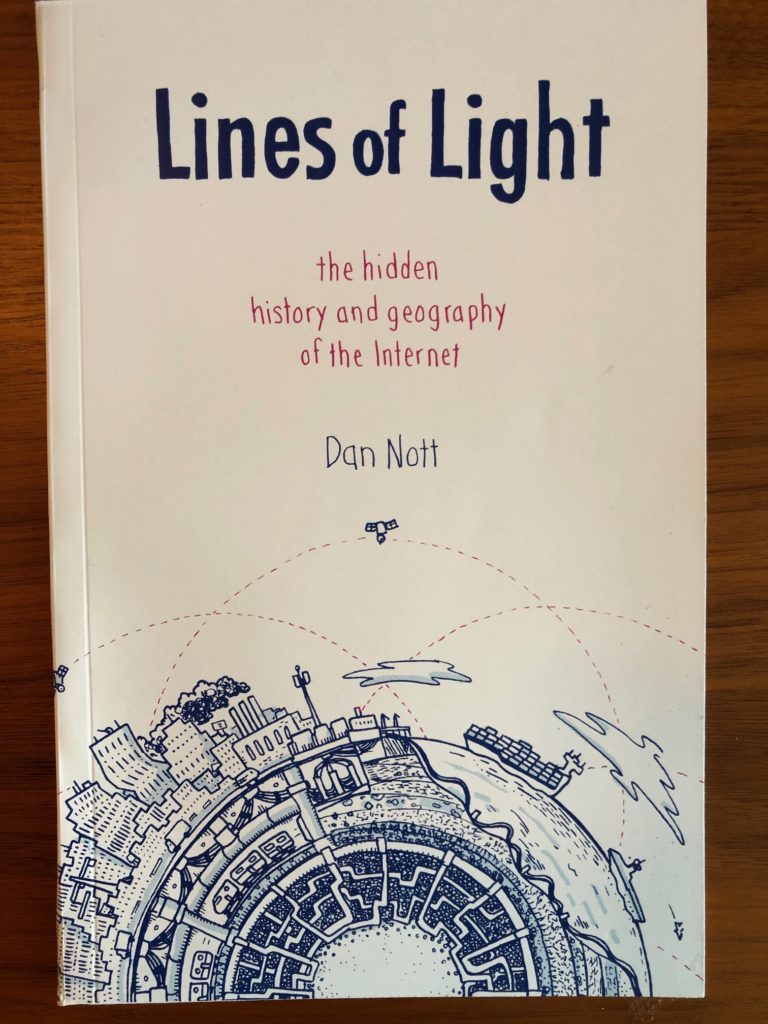

In my online “CyberWar and Espionage” class I show a famous clip of President Bill Clinton talking about China’s efforts to censor information online (p. 76). He wished them well with that, and said that it was similar to trying to nail jello to the wall. Over the years I have noticed that this footage often infuriates students -especially international students- who view it as an example of American hubris. Of course, in the years that followed not only did China successfully create an entire digital ecosystem, it also managed to successfully control critical information. And China’s example has since been followed by a plethora of authoritarian or authoritarian-leaning states (p. 7). But what strategy did China use to achieve this seemingly impossible goal? This question is at the heart of Robert’s insightful and carefully researched book, Censored: Distraction and Diversion Inside China’s Great Firewall.

In essence, what Roberts argues is that the standard approach to censorship -which relies on fear- would no longer work in a digital era: “The costs to governments of fear-based methods of censorship are more severe in the information age, as there has been an increase in the number of producers of information in the public domain” (p. 54). Instead, she argues, China adopted “porous censorship.” This does not mean that China can delete all negative information. Instead, China’s approach has been to raise the costs of information (which she terms “friction”), by imposing what equates to a tax on time or effort (p. 2, 42). What this means is that elites are often able to invest in technology (such as Virtual Private Networks) that allow them to escape the limits of censorship, while the masses cannot (although there are risks even with VPN usage. See p. 163) Still, this approach achieves two goals. First, it creates a division between the elites and the masses (p. 6, 8). Second of all, it avoids popular anger or backlash, when people realize that information is being censored. If people don’t understand that a particular web page takes four times as long to load as a deliberate policy, they are less likely to become irritated (p. 121-122). At the same time the government can promote other information (flooding), which can distract from the negative content that they want to obscure (p. 5-6): “Friction and flooding are more porous but less observable to the public than censorship using fear, and therefore are more effective with an impatient or uninterested public” (p. 18).

What Roberts is trying to do is to explain how a government can simultaneously have a digital environment which is ubiquitous, while also limiting information that might undermine the regime. Her work achieves this goal, and explains why a regime such as China does not target absolute censorship (p. 4). Censorship doesn’t have to be perfect to achieve its goals (p. 4). By concealing censorship the government minimizes its costs, which include drawing the attention of its citizens to certain topics (p. 8).

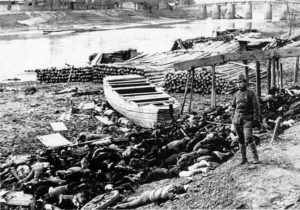

Roberts prose is at times prolix. There are moments where she repeats ideas or elaborates on examples, when a more concise treatment would have worked as well. But the book also rewards attention. At the core of her work is a detailed look at censorship in China, which is based on pain-staking research on such topics as how the Chinese states censors information about the immolation of Tibetan monks (p. 19, 155-162). Her ability to digitally scrape information from the Chinese online environment is impressive, and her analysis of this data is rigorous (see for example pp. 122-145). While this allows us to have a deeper understanding of China’s digital world, what’s even more significant is how she develops a theoretical understanding of censorship. This allows not only to better understand the choices made by the Chinese state, but also other forms of censorship in democratic countries (p. 16-17).

Most of all, the book creates a new perspective of censorship, which breaks down simple binaries of free and unfree. Yes, there is censorship in China. But the notion of “porous censorship” allows us to understand how the Chinese state achieved the seemingly impossible, and created an effective censorship apparatus for a fully digital citizenry. Of course, this system has an authoritarian underpinning. Google was eliminated, and a uniquely Chinese digital environment created (p. 55-58). The Great Firewall blocks key websites (p. 109). But most Chinese don’t necessarily perceive that they are living in a heavily censored world (p. 25, 110, 150, 165). They can find information online. The Chinese equivalents to YouTube and Twitter work for them. And sometimes they unleash scathing criticism of government officials or policies (p. 113). But censorship is also pervasive: “For typical Internet users, the government uses the strategy of porous censorship to walk the fine line of controlling information while preventing censorship from backfiring” (p. 115). The laws regarding what citizens can post to the internet prohibit a wide array of information (p. 117). All social media in China requires that citizens sign up using their real names (119): “Previous studies have estimated that anywhere between 1 percent and 10 percent of social media posts are removed by censors on Chinese media social sites” (p. 151). There are clear limits on expression, but the government tries to conceal these restrictions as much as possible.

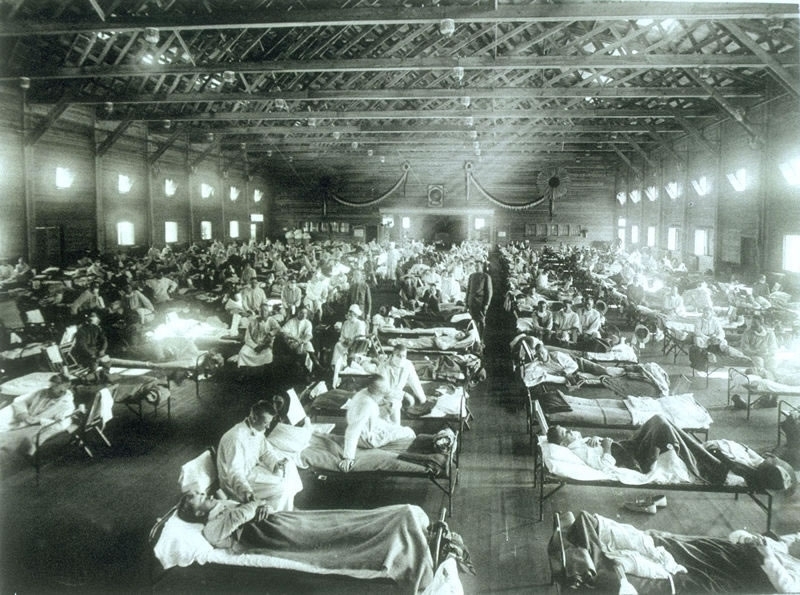

The velvet glove has worked effectively, even though during a crisis -such as in Wuhan during the early COVID-19 outbreak- fear still remains an important tool, particularly for “journalists, activists and key opinion leaders” (p. 116; see also 119). Roberts argues that although it is an effective strategy, porous censorship can be a destructive approach for a regime when faced with a crisis (p. 10, 14). But it’s also true that China’s regime has to date effectively overcome multiple major crises, including the February 2020 Wuhan debacle.

Two decades ago it was widely believed that the rise of the internet would undermine authoritarianism globally (p. 12). That didn’t happen. As Roberts describes, “political entities have a wide range of effective tools available to them to interfere with the Internet without citizens being aware of it or motivated enough to circumvent it” (p. 13). But she also describes the “dictator’s dilemma,” namely that censorship comes with costs, one if which is that increases the likelihood that the regime will become too distanced or out of touch with its populace (p. 22-23, 52, 111). This rich work of political science scholarship describes how China has sought to resolve this dilemma, so far with remarkable success. Of course, there are economic and political costs to this approach (p. 76). But in the end, China has created a nuanced and layered strategy to control digital information, as Roberts thoughtfully details. I think that this book would be an excellent choice in undergraduate senior seminars and graduate classes that address censorship or authoritarianism.