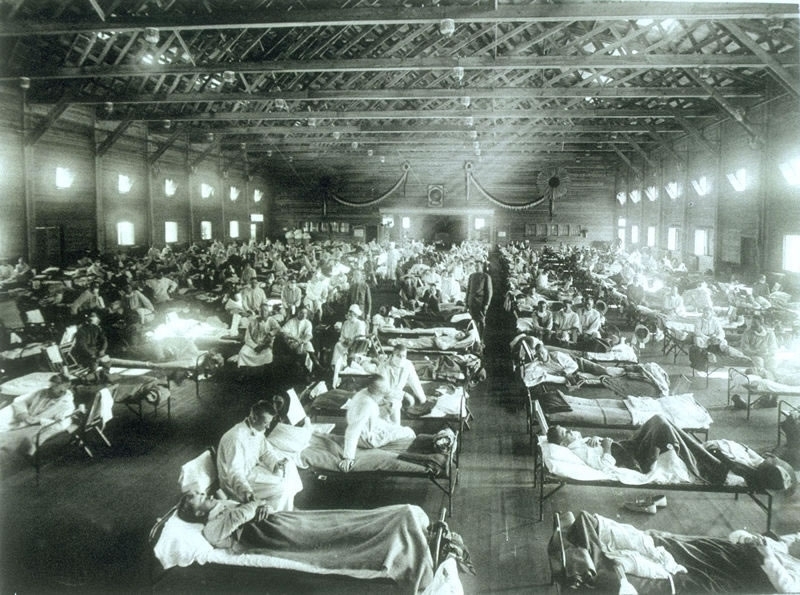

After the wonderful histories of Alfred Crosby and John Barry, readers might wonder if there is truly anything new left to write about the 1918 influenza pandemic, which killed between 50 and 100 million people world-wide, at a time when the world’s population was much smaller. Laura Spinney’s detailed, beautifully written and insightful work shows how much study can yet be done on this topic.

As Spinney describes in the opening to her book, in the 1990s much of the writing on this pandemic had been done on Europe and the United States. Of course there were exceptions. In Canada Eileen Pettigrew created a rich narrative of people’s experiences from survivors accounts, while Betty O’Keefe and Ian MacDonald told the story of how medical officer Fred Underhill fought the disease in Vancouver, Canada. There were similar accounts of popular experiences with the pandemic in other countries, such as Australia and New Zealand. But voices in Asia, Latin America and Africa were often not included. Since the 1990s there has been a plethora of work in many different nations, at the same that scientific advances have made it possible to have a much better understanding of the pandemic.

Spinney’s history takes full advantage of this study. She also has a gift for seizing upon the lives of individuals to tell a broader story, whether it was a young man in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil or a scientist in Republican China. She weaves together these narratives to create an overarching view that is truly global. After reading the work I find myself curious to learn more details on individuals, such as a woman affected by the pandemic in South Africa, who then created a religious (and perhaps millenarian) movement.

While such individual accounts are powerful, I particularly like chapter fifteen, in which she described how the same virus had dramatically distinct impacts in different places. Why would the same disease cause mortality rates in excess of 80 percent in some remote Alaskan and Labradoran villages, and far lower rates elsewhere? Of course, the flu was not unique in this respect. I wrote an entire book trying to understand the diversity of HIV epidemics in Latin America. What is perhaps most striking to me is that after a century of earnest study, many of these questions remain unanswered.

What is clear was that the pandemic utterly devastated some locations. In Western Samoa, twenty-two percent of the population died. In the Pacific, on the island of Vanuatu perhaps 20 languages died because of the heavy mortality that the virus brought. Given Brazil’s catastrophic response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the disproportionate impact that the virus is having on Brazil’s Indigenous peoples, might something similar happen in the Amazon rain forest now? As Spinney states, there was a strange paradox to the virus. Cities often saw high mortality rates, but isolation caused terrible vulnerabilities in remote communities.

What was also striking to me was her discussion of the influenza’s aftermath. In part, this was reflected in such societal trends as a loss of faith in science. Will we be struck by a similar trend with COVID-19? But there was also a physical legacy of the virus, as many people suffered either psychological trauma over the loss of loved ones, or debilitating physical effects that lingered long after the virus was gone. Of these, perhaps the most famous was encephalitis lethargica. While it cannot be proven that the 1918 influenza pandemic caused this disorder -again so much remains unknown about this tragedy- the onset of the one was accompanied by the emergence of the other, as some people remained paralyzed -but apparently aware- for decades. Will COVID-19 have similar health effects that linger for more than a generation? The thought is chilling, given that one recent pre-publication from Korea just reported that up to 90 percent of COVID-19 survivors still report symptoms months later.

Still, what most struck me is that we are now having the same debates now that we had over a century ago: “One 2007 study showed that public health measures such as banning mass gatherings and imposing the wearing of masks collectively cut the death toll in some American cities by up to 50 percent (the US was much better at imposing such measures than Europe).” While now it is the US struggling to persuade its citizenry to wear masks, there is a haunting quality to the debates from this time. Some challenges that faced public health authorities then echo during the COVID-19 pandemic now, although (as far as I know) the death threats and public vilification of public health leaders was uncommon in America a century ago. So perhaps things have gotten worse. Spinney’s last two chapters are remarkably prescient for a book that was published in 2018.

I’ve spend much of the last twenty years working on public policy and infectious disease, first with my book on HIV/AIDS, and more recently with Zika and avian influenza. Some factors are constant, such as the fact that conspiracy theories emerge with every pandemic. One of the most common human urges when faced with an outbreak is to find someone to blame. But what depresses me is that I don’t think the historical studies or public policy achievements make much difference in the long run. In 2018 I published an article on wet markets in Hong Kong, which recommended that the special administrative region consider closing them. Of course, COVID-19 did not emerge in Hong Kong, but likely from a wet market in eastern China. One of the reasons that I hate conspiracy theories is that the distract from the real actions that could make people safer. They also make pandemics and outbreaks seem mysterious and unpredictable.

In fact, people have been studying coronaviruses in China since SARS emerged in 2003 precisely because such an event might take place. This was entirely predictable. As I said in an earlier blog post, how much human suffering might have been avoided if China’s wild game markets -which particularly cater to an older and wealthier clientele- had been closed. Yet even the Chinese government -with all its power and influence- either would not or could not do this. And now social media accounts spread tales that this outbreak is caused by 5G, and people in Britain burn cell towers. Two million people have died globally and winter is drawing closer in the northern hemisphere. We all know what happened in November 1918. Now we must now hope that a different virus will have a dissimilar impact.

Yet behind the scenes scientists have laid the groundwork that will allow for vaccines to be more quickly developed, because much basic science work has been completed. For all the frustration with sciences’ failures and limitations, the hope that we have now doesn’t come from conspiracy narratives -which don’t lead to any constructive steps- but from the often ignored work by nearly anonymous scientists in global laboratories. This work lacks the drama of the conspiracy theories, but the time-consuming and methodical study has laid the groundwork for the greatest vaccine push in human history. Conspiracy theories are easy to create. Real public policy or scientific advances are far more difficult, time-consuming and (often) difficult to understand. Spinney’s work is built upon a detailed examination of both the historical and scientific literature that has been built up over the last century, particularly the last twenty years.

It has long gone out of fashion in academia to look for lessons or a moral in history. But if this line of thinking is taken too far, it might lead people to question the value of history entirely. If historical study cannot give us lessons for the present period, isn’t it little more than a hobby for the affluent few? Laura Spinney’s brilliant book shows how a careful understanding of history can provide us the context to better understand current challenges. Sadly, in this current moment, it’s probably difficult to interest people in reading a work about a past outbreak. Spinney’s magisterial, carefully researched and beautifully written book deserves a broad audience. Highly recommended.

References

Spinney, Laura. Pale Rider : The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World. First US Trade Paperback ed. New York: PublicAffairs, 2018.

See also the following works for more reading on this topic.

Barry, John M. The Great Influenza : The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. New York: Viking, 2004.

Crosby, Alfred W. America’s Forgotten Pandemic. West Nyack: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Canadian popular histories:

O’Keefe, Betty, and Ian Macdonald. Dr. Fred and the Spanish lady: Fighting the killer flu. Heritage House Publishing Co, 2004. (Full disclosure: this press also published my history of an evil spirit in Algonquian belief. Please note that I have no control over the price of physical copies of this book on Amazon, which sometimes surges to hundreds of dollars for mysterious reasons. So if you click on this link for my book, please don’t send me unhappy emails to complain about the book’s price).

Pettigrew, Eileen The silent enemy: Canada and the deadly flu of 1918. Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1983.