BSE was a classic example of an iatrogenic disease, which is an illness created by humanity itself. The disease is caused by a prion, which is not a living thing. Prions are strange. It’s believed that they are malformed proteins, which can trigger other proteins to similarly mis-form. This creates a terrible cascade that impacts the brain, thereby causing neurodegeneration. They are also incredibly resistant to heat, so they do not readily break down during cooking, which would eliminate the risk of most pathogens and helminths. Once a living organism such as a person is infected, there is no known treatment for the disease.

Until recently, health authorities and governments have assumed that people were unlikely to be affected by Chronic Wasting Disease. There is now evidence that this might not be true. In a recent article titled “New Research Sparks Health Canada Warning Deer Plague Might Infect Humans” in the Tyee, Andrew Nikiforuk discussed the latest scientific study on this issue. Stephanie Czub with the Canadian Food Inspection agency exposed macaques to infected material by a variety of mechanisms. As Nikifork described, macaques became infected by eating infected food, as well as by injection. Czub used macaques, because as primates they might have a similar biology to humans.

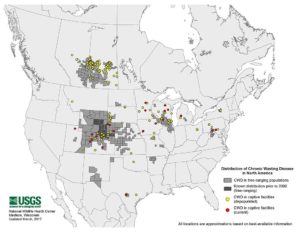

As a result of this study the Health Products and Food Branch of Canada has issued a warning that it might be possible for humans to be infected by CWD, and that people should avoid eating infected animals. How exactly people are supposed to know which animals are infected -as at an early stage that do not show symptoms- is not explained. This will be particularly difficult for northern citizens, particularly Indigenous peoples, who rely on deer, moose and elk as a basic food source. The reality is that thousands of people are currently consuming infected animals. There is currently no treatment for prion diseases of any kind. It’s also significant that the disease can be spread by body fluids, such as urine, that hunters may use as bait. The Alliance for Public Wildlife has a great paper, “The Challenge of CWD: Insidious and Dire” that explains how authorities should respond to this threat.

While these recommendations are critical, it’s also important for governments to strengthen overall safety regulations of the food industry, as well as cross-border trade in food and livestock. Lax regulations may have contributed to these food threats, which are much easier to prevent than address afterwards. It’s also important to remember that so far nobody has been diagnosed with CWD; at this point the risk is theoretical. Still, lax regulation, insufficient vigilance, and poor documentation have allowed CWD to spread geographically across national borders, which will have long-standing and expensive consequences. Health is part of a social context, which includes food production. A better-funded and rigorous approach to the international regulation of both domestic herds and game food production would limit the introduction of similar pestilences in the future, as well as help to contain CWD.

- Schwartz, M. 2003. How the Cows Turned Mad. Trans. E. Schneider. Berkeley: University of California press.

- Fischer, J.W.; Phillips, G.E.; Nichols, T.A.; Vercauteren, K.C. (2013). “Could avian scavengers translocated infectious prions to disease-free areas initiating new foci of chronic wasting disease?”. Prion. 7 (4): 263–266. doi:10.4161/pri.25621

- Haley NJ, Hoover EA. Chronic wasting disease of cervids: current knowledge and future perspectives. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 2015;3:305-25

Shawn Smallman, 2017