Nüshu: the secret language of women in ancient China

Imagine that you are an upper class Chinese woman living in a rural Chinese province in the 1600s. You live an isolated life. Your feet were bound from childhood, so that you could not wander or engage with people outside your household. You spend your time in the north room of a house, where you embroider all day, and are kept isolated from others. You have no formal education, and it seems difficult to communicate with other women, and perhaps it is impossible to have any private communication. What do you do?

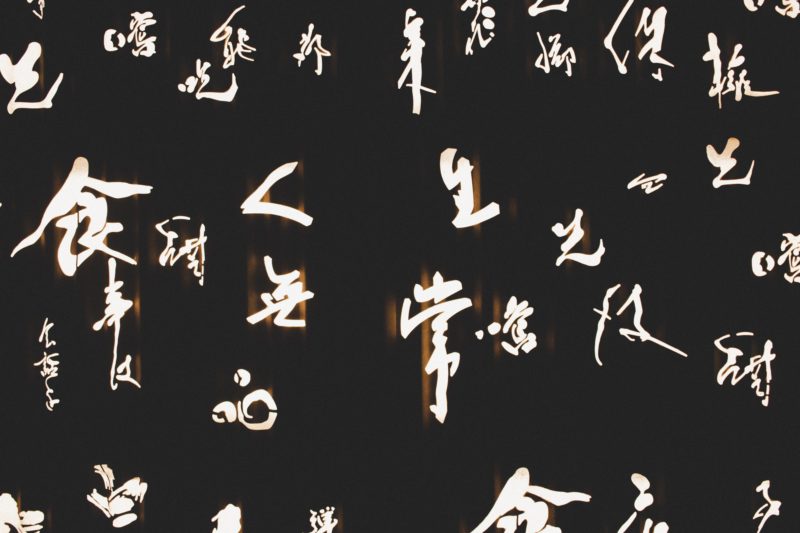

If you were a member of one group of Chinese women, you would create your own secret script, which could only be read by other women. We will never know the names of these innovators, but they created their own literary world with an invented writing system, Nüshu. As many scholars have noted, this may be the only script in the world that was intended only for women.

What is most remarkable to me about this language is not only that it existed, but also that it has endured. Indeed, a new documentary called Hidden Letters, directed by a Chinese woman named Violet Feng, which describes how people are now trying to revive this language. In addition, there is a wonderful wonderful podcast episode by Rebecca Kanthor for the World, in which you can hear how Nüshu (which means women’s book) has been appropriated by other actors, who now use it to teach women how to behave according to traditional etiquette. It has even appeared in a KFC commercial- really! But the enduring legacy of this script is its memory of how it created a shared community of women using text written not only in letters, but also on personal objects such as scarves.

If you are interested to learn more, you can also listen to Lazlo Montgomery’s history of this secret writing on the Chinese History Podcast. Or if you are curious to read a novel on the topic, Lisa See has a new book based on this history titled Snow Flower and the Secret Fan. This website for the the book says: “A language kept a secret for a thousand years forms the backdrop for an unforgettable novel of two Chinese women whose friendship and love sustains them through their lives.”

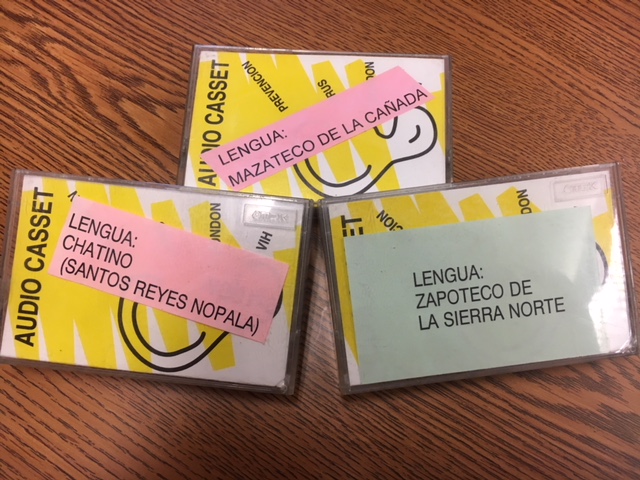

What’s interesting to me that new secret writings continually appear. Today in China people try to evade censors on WeChat by using codes for certain key words, often by relying pinyin that has been shortened to just a couple of key letters. Women have developed their own shorthand for key words (such as husband) to try to keep some conversations confidential. Other Chinese people choose to speak in their home villages’ local dialects when making video calls on WeChat (and talk very quickly) in the hope of evading censors. In some ways this is not dissimilar from what young people do with their texts in Europe or the United States, as emojis and acronyms convey new -often sexual- meanings.

The last known native writer of this women’s language, Yang Huanyi, died in central China in 2004, when she was perhaps 98 years old. She was a graceful and fluid writer, who published a book of prose and poems the year of her death. At this point the writing system was at least four centuries old, although some argue that it is based on a far older writing system, as the article at the link above suggests: “Some experts presume that the language is related to inscriptions on animal bones and tortoise shells of the Yin Ruins from more than 3,000 years ago, but no conclusions have been reached as to when the language originated.” If so, how long did this unusual women’s writing system truly exist?

What is also remarkable is that hundreds of examples of this writing survive. The texts were not meant to outlive the reader, as this article also described: “Nushu manuscripts are extremely rare because, according to the local custom, they were supposed to be burnt or buried with the dear departed in sacrifice.” So this ancient writing system, which was designed to be ephemeral, has been adapted into a new Chinese world, where it now appears in places as diverse as pop culture and scholarship.

I want to learn it.