The terrifying wildman of Canadian folklore

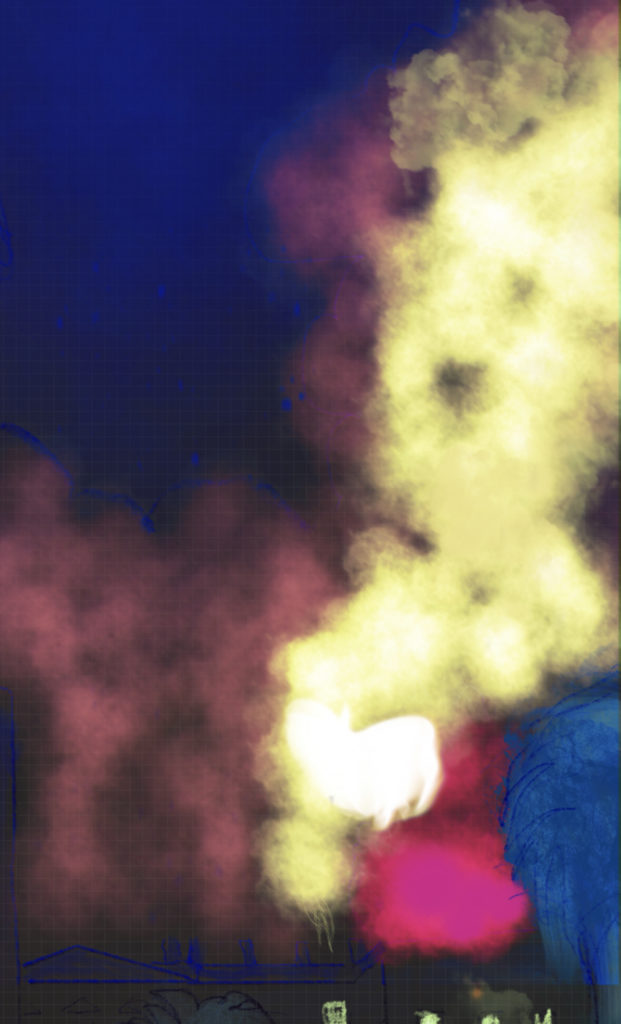

Picture credit: Elle Wild took this photo of the Indigenous graveyard in British Columbia, Canada during the 2020 wildfires. Used with permission. I wonder if the second totem pole from the left has an image of Dzunukwa, the Basket Ogress, on the base?

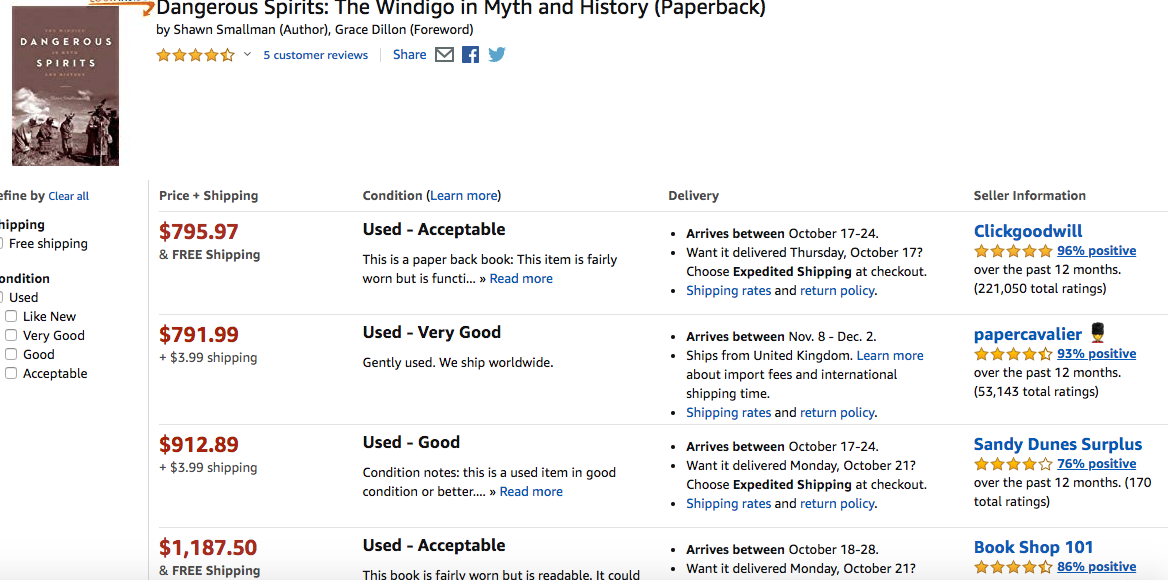

Every year I cover some aspect of the supernatural around Halloween. This year I want to talk about video by Hammerson Peters, a Western Canadian author who has a YouTube channel covering that country’s legends. These videos are well-produced and draw on historical sources. I love folklore, and have written my own book about an evil spirit in Algonquian belief called the windigo. So, of course, I enjoy viewing his channel, including one recent video: Nakani: The Wildman of the North.

In this video he Peters draws on careful research to document Indigenous belief in a being similar to the Sasquatch or Bigfoot in the Northwest Territories and Alaska. He also touches on similar tales from other areas, such as Labrador. His use of the records of 19th century explorers deepens the sense of veracity in this narrative.

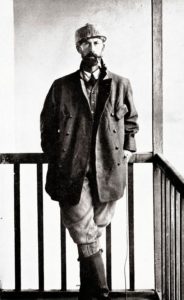

The video makes wonderful viewing on a windy, fall night, and I recommend it. But the curse of having done work on mythology and folklore is that I have some context regarding some of the sources that he uses. For example, Hammerson Peters refers to one case documented by a French Oblate Missionary, Émile Petitot (1838-1916). When considering information the first step is always to evaluate the source. There are question marks surrounding Petitot: “Beginning in 1868 Petitot began to have short bouts of insanity in the winter; he hallucinated, ran half naked in -40 degree weather, and attempted to kill Father Séguin” (For Petitot’s mental health issues see the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio.php?id_nbr=7649). The priest also had a public relationship with a young male servant, followed by a marriage to a local Métis woman, Marguerite Valetta, in 1881; the Catholic Church then forcibly placed him in a mental asylum in Montreal in 1882. …