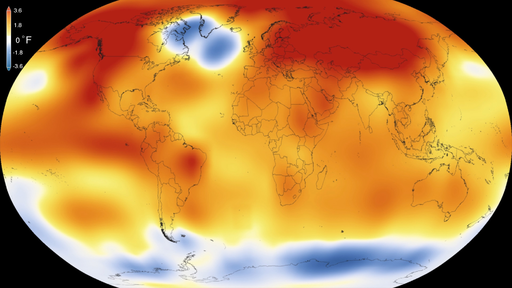

Andrew Nikiforuk’s article “Tree Teachings: How Forests and Wildfires Are Critically Linked,” examines the work of botanist, Diana Beresford-Kroeger in order to understand wildfires. The strength of this piece is its ability to describe the biological globalization that is impacting forests, as plants from one region move to another. In Portugal one of the reasons that fires may have caused such damage was that people had turned to the plantation farming of eucalyptus. The piece also shows the infinite connections between forests and other environments including -surprisingly enough- their impact upon the oceans themselves. If one is interested in the cultural impact and meaning of forests, the second article in the series, “Tree Teachings: How Fossil Fuels and Climate Change Are Altering the Global Forest,” examines changing forests from North Africa to New Zealand. So globalization may be one of the factors –along with climate change– that is fueling these fires.

The question is what to do about it. I particularly like Yvette Brend’s article in the CBC about Annie Kruger, an Indigenous fire-starter in Canada, who was the last person to hold that role in her community. Until the 1930s her people would regularly burn the land to improve fertility and prevent massive fires. As most people are now aware, the effort to suppress fires that followed this period led to forests being massively over-burdened with dead or damaged trees. There is too much fuel. Of course, it’s not so easy to set smaller controlled fires. I wonder if all the practical knowledge of the Indigenous fire-keepers has been lost? Now more than ever, we could use some experienced guides in places like Canada. This approach has even been tried by Australia. But all these efforts have been on too small a scale. Of course, without addressing global warming, no such measures will work, and the planet’s future is bleak. Still, perhaps Indigenous approaches can help be part of the solution.

I first wrote this blog post in June of 2019, but after viewing coverage of Australia’s terrible fires in January 2020, I am updating it with this final paragraph. One of my favorite authors is Elizabeth Hand. In her short-story collection, Fire , she has an eponymous short story. The work describes a small group of people trapped by what they calls a megafire, which is drawing closer. The fire is so severe that burning birds dropped from the sky, people found it difficult to tell the night from the day, and the fires created their own winds. When I read the story recently, I wondered how she could have so clearly imagined what is happening now in Australia. If we don’t act, I fear that people in the North American west, Australia, and many other regions will see the world evoked in Hand’s story.

Hand, E. (2017). Fire. (PM Press outspoken authors series). Oakland, CA: PM Press.