Shane Harris, @ War

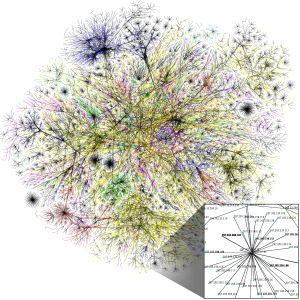

With the constant media attention to the alleged Russian involvement in the last American election, there is perhaps more media attention to the issue of cyber-warfare than ever before. In this context, Shane Harris’ book, @ War: the Rise of the Military-Internet Complex is provides a sweeping overview of how the U.S. government and its corporate allies have sought to respond and use cyber tools for espionage and war.

Harris has a background as a journalist, and he has extensively interviewed people in both the U.S. federal government and industry. His work provides a deep understanding of how these actors view cyber-conflict. The book is particularly good at showing how corporations are intricately connected the armed forces in cyber-warfare: “Without the cooperation of the companies, the United States couldn’t fight cyber wars. In that respect, the new military-Internet complex is the same as the industrial one before it” (Harris, p. xxiii).

At the same time, this book views this issue through an American lens, and at times has an unreflective view of technology’s role in war. Ever since the Vietnam War, the United States has relied on technology to win wars, while not similarly prioritizing cultural, strategic and historical awareness. One can see this issue in the opening section of the book, which examines U.S. efforts to use cyber-espionage to target ISIS in Iraq, in what he describes as a triumph: “Indeed, cyber warfare -the combination of spying and attack- was instrumental to the American victory in Iraq in 2007, in ways that have never been fully explained or appreciated” (Harris, p. xxii). Even though his description of U.S. operations in Iraq is fascinating, this part of the work has not aged well, and confronts the reader with technology’s limitations more than its capabilities. …