As I write this blog post all travel has been banned in Wuhan, and two neighboring cities (Huanggang and Ezhou) in China. The cause for this travel ban is a novel coronovirus, which is currently called nCoV2019, although it will likely receive a new name soon. Coronaviruses are a virus that causes respiratory diseases, such as SARS in 2003, and MERS in the Middle East. SARS was a bat virus that passed through a civet cat at a Wet Market, and then jumped to humans. Although the outbreak was ultimately brought under control, it was contained at a very high cost. The Fighting SARS Memorial pictured above commemorates Hong Kong health care workers who died while serving their patients.

Wet markets are places where consumers can view and purchase living animals, who are then slaughtered on site for them. There are multiple issues with these markets. One is that they bring diverse living animals together, so that viruses can jump from one species to the next. Another problem with wet markets is that tissues can be aerosolized, such as when poultry is de-feathered or when animals are slaughtered. These wet markets have been associated with outbreaks of not only SARS, but also avian influenza. I’ve argued in an earlier paper that these markets should be shut down in Hong Kong. That hasn’t happened. Some travel advisories now say that visitors to China shouldn’t visit wet markets. This is shutting the barn door after the horse has left. It’s too late now. These markets should be shut down, for the sake not only of China’s health, but also for global health. One argument measure against this is that such markets are a part of traditional Chinese culture. But other Asian countries have ended this practice for health reasons. But that matters more for the future than for this moment.

The challenge now is that this is the lunar New Year and hundreds of millions of Chinese will be traveling. Of course there are the new travel restrictions in Wuhan and two neighboring Chinese cities. But this seems to be a very different situation to that of 1918 with Spanish flu. That year John Martin Poyer quarantined American Samoa, which escaped the pandemic. In Western Samoa, in contrast, perhaps 22% of the population died after a ship traveling from New Zealand, the S.S. Talune, brought the pandemic. But those were isolated specific islands. There is currently a heated controversy about the value of these quarantine measures. But the virus has already been reported from Brisbane, Australia to Washington state in the United States. And Korea, Hong Kong and a myriad of other places. Quarantine might slow the spread of the virus, but is not going to stop it. That’s no longer possible within that country.

There are also heated conversations -with strong opinions on both sides- regarding measures such as airport screening. The United States, for example, has implemented airport screening at three airports which have flights to Wuhan. Globally, airport screening has caught some people with nCoV. The people opposed to it say that it only captures people with fever. Those who favor it acknowledge this, but also say that it is a useful tool, which has become much more effective since SARS in 2003. Still, it is a not a perfect tool, and more cases will come.

There are multiple efforts to develop a vaccine now. I am not a scientist but a social scientist, who studies the history and public policy around infectious disease. I still think that it’s worth remembering that historically vaccines often take years -or decades- to develop. It’s not like in the movies in which a vaccine is developed in a few weeks and the world is saved. Even after a vaccine is developed, it must be tested for safety, and then manufactured at scale. In the case of the 2009 H1N1 influenza outbreak most of the vaccine became available after the pandemic had already peaked. And that was for influenza which -for all its many tricks and challenges- is much better known. It is likely that a vaccine against this virus will take longer to develop, and will only be available after the first wave of the pandemic has run its course.

There is a lot of discussion about the virus’s lethality. The fact is that right now we just don’t know. In 2009, the H1N1 influenza outbreak generated a great deal of fear (and conspiracy theories) but in the end the mortality rate was not dramatically greater than seasonal flu. It’s too soon to now if that will be the case with nCoV. On the one hand, health care experts want to avoid a panic. On the other hand, it’s not necessarily only good news is this virus is somewhat less deadly than SARS. One of the factors with SARS that perhaps made it easier to distinguish was that its symptoms were distinct. If this virus sometimes is relatively mild, so that it might be hard to distinguish from flu, that might make it more difficult to identify and contain. As many people have commented, we are currently in peak flu season. In many parts of the world, the 1918 influenza pandemic had a mortality rate of around one percent (in some locations far higher) but between fifty and a hundred million people died globally. We will know much more in a few weeks.

One thing that we do know- so far fairly few children have been infected. Is this an artifact, or some strange aspect of the virus’s biology?We don’t know. Those who have died have been older, and often have suffered from pre-existing conditions. They have also mostly been males, be a factor of almost three to one. But one must be cautious interpreting all this data, because it is quite early in the pandemic. Lastly, the virus does seem to spread relatively well among people, which was not apparent at the start of the outbreak. So far fourteen (some question about this number) health care workers have been infected.

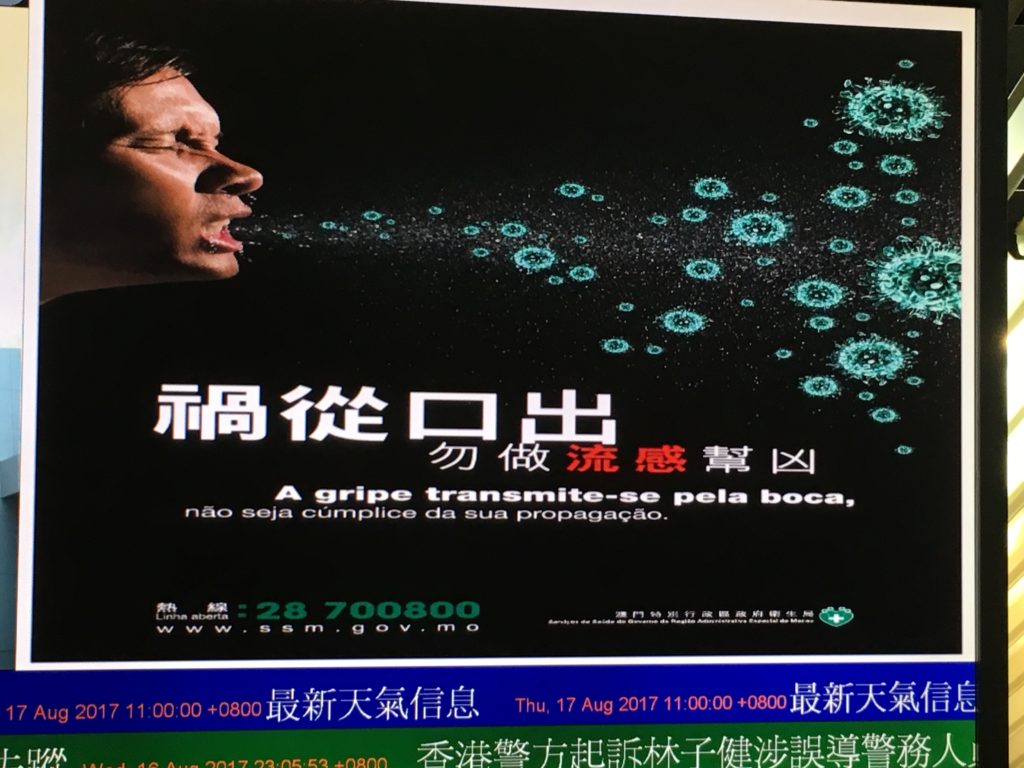

One common thread often heard within the infectious disease community is that China is responding very quickly and transparently to this outbreak. We are light years ahead of the situation in 2003. The virus was picked up with amazing speed. Some genetic analyses suggest that it only emerged in humans in December 2019. How it was detected during flu season is very impressive. There is some coverage that some people who were infected -such as one family with multiple cases– were not treated well. For all China’s efforts, it seems that local health authorities are struggling to cope. If this virus spreads to some parts of Africa, with which China has growing trade and business relations, it will be difficult for poorer countries to contain. It’s also true that China has made vast investments in public health, including screening and education. Anyone who has traveled in China has seen screening centers and airports and borders. And posters and information about avian influenza and MERS are present in a way that they wouldn’t ever be in the United States or Europe.

As I’ve talked about so many times on this blog, with every pandemic there are conspiracy theories, such as was the case with the Zika epidemic. I have already seen these conspiracy theories appear on Twitter. These theories are not harmless, because they shape peoples’ behavior. If people believe that this outbreak is a biological weapon, they may not trust health advice from their own government or health authorities. Please rethink spreading these narratives.

We are just at the beginning. There is so much that we don’t know. But we will know so much more in three or four weeks. If you want some reliable sites for information, I recommend the Virology Down Under blog by Ian MacKay. The Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) is also another key website. Lastly, Michael Coston’s Avian Flu Diary covers far more topics than avian influenza, and is a good resource. Lastly, this website in China provides good information on the outbreak there.

As many others have said, if nothing else please be sure to get your flu shot this year. This will help you to avoid the danger of co-infection, and perhaps keep you out of the doctor’s office or the hospital during this time. If nothing else, it might safeguard your health regardless of this pandemic. And if -like me- you have asthma, or if you you are over 65, you might consider asking your doctor about the adult pneumococcal vaccine. The majority of people who are infected by coronavirus die from pneumonia. While we don’t have a vaccine to prevent the original infection, this vaccine might prevent you from developing a secondary bacterial pneumonia. As was the case as long ago as the 1918 influenza pandemic, very often what kills people with a viral respiratory infection is a subsequent bacterial pneumonia. And even if you are never infected with this coronavirus, if you are in a risk group this vaccine might protect you after other illnesses, such as seasonal flu.

Lastly, you can read my blog post about quarantine and nCoV, which is based on the historical context provided by the 1918 pandemic.