As I write these words nurses in Hong Kong are on strike to protest the fact that the Chief Executive, Carrie Lam, will not close the border to China. To be clear, the executive has sharply restricted entry to Hong Kong, closed most crossings, and forbidden entry from the most affected Chinese state, Hubei. But there are still strong calls for a complete border closure coming from within Hong Kong’s medical community. Similarly, the United States has restricted flights from China to U.S. citizens only; some U.S. airlines had already canceled service to China. All such quarantine measures are controversial.

On social media, such as Twitter, and in the press, a number of experts have denounced all quarantines as being not only ineffective but also in violation of WHO guidelines. These authors worried about panic overcoming good judgement, the economic costs of restricting travel, the stigma imposed on those from affected areas (Chinese in particular, but also all Asia), and the importance of upholding International Health Regulations. These are valid and important points. Some authors have also pointed to studies based on computer models showing that quarantines are ineffective with highly contagious respiratory diseases.

Recently the tone has shifted in the discussion, as it has become clear that some cases of the virus are being spread asymptomatically. The number of cases has grown quickly. Some apparent facts (such as no human to human transmission) that seemed true in mid-January are no longer true. So the stridency of the debate about quarantine has declined, but the debate continues.

So is there any role for quarantines to manage such a pandemic? And is there some other way to make a judgement that relies less on computer models? I would suggest that looking at the past history of respiratory pandemics, such as the 1918 influenza pandemic, might be useful. Can history suggest particular circumstances in which quarantines may work?

In 1918 perhaps fifty to hundred million people died in an influenza outbreak. While perhaps one to two percent of the global population died in that pandemic, in some communities the death rate was much, much higher, such as Indigenous communities in Alaska, the United States or Labrador, Canada. The Newfoundland Archive has made a video, The Last Days of Okak, freely available. The video tells of what happened when the 1918 influenza arrived at an Indigenous community in Labrador. It is not a video for the faint of heart, or one that should be viewed by anyone feeling depressed. The description of how dogs responded after days without feeding them is disturbing. Yet the words are the survivors are worth hearing, because they demonstrate the disproportionate impact that a virus may have in remote communities.

The reason that I am discussing Labrador is that all this suffering was introduced by one ship traveling from the Canadian province of Newfoundland. I’ve recently been reading Anne Budgell’s new book, We All Expected to Die: Spanish Influenza in Labrador, 1918-1919. Budgell begins by tracing the history of how how various epidemic waves had washed over the Indigenous peoples in the decades before 1918. It’s grim reading, and makes one wonder how anyone in Labrador survived measles, tuberculosis, diphtheria and scarlet fever. But it was the introduction of influenza that sealed the fate of two communities, which had the highest death rate recorded from the 1918 pandemic. Budgell’s work is a story of heroism, as people rallied to face the nearly unendurable. And for generations people have remembered the name of the ship that brought the virus to Labrador, the Moravian supply ship Harmony. Her book also makes the point that not all communities will be equally impacted by a pandemic, in part because of health inequalities. To me, her work suggests that in isolated communities, islands, and areas with weak health care systems, quarantine can be a worthwhile tool. It’s not as simple as a statement that quarantine works or it does not.

Perhaps the best historical example of this was the case of Western Samoa and American Samoa in 1918. A single New Zealand ship, the Talune, arrived in Western Samoa on November 7, 1918. This moment started the epidemic. In the space of perhaps one month one quarter of Western Samoa’s population died in the epidemic. According to Tomkins (1992, p. 181) the island lost 22% of its population in a matter of weeks, and no south Pacific island lost less than five percent of its population. The ship’s arrival has been a painful memory for over a century on the island. Much of the discussion has focused on whether the colonial administration (Tomkins, 1992, p. 182) bears the responsibility for the disaster.

In contrast to the experience of Western Samoa, in American Samoa the local executive (Poyer) decided to implement a quarantine (Tomkins, 1992, 184). It worked. The island was spared the disease. Poyer was a naval officer who was willing to take extreme measures to implement the quarantine. As Tomkins describes (1992, 184) he even used shore patrols to keep out refugees fleeing the disaster on other islands. According to Tomkins, history has looked favorably on the decision since the island escaped the disaster of Western Samoa. Tomkins (p. 184) also points out that a maritime quarantine in Australia seems to have saved the country from the pandemic until 1919, when a less deadly wave finally arrived. As she states (1992, p. 184) Australia’s death rate was ultimately less than that of Mauritius.

The point of this history is that quarantine can be a tool that is effective in some circumstances, even with highly contagious respiratory diseases. It can protect isolated communities, buy time to develop health care capacity, and ensure that not all areas face the pandemic at the same time. But it is also of little use (or less important) in other circumstances, such as when there are no clear, natural barriers, health care systems are effective, populations can readily move, etc. The examples I have given are horrific examples, and these experiences are atypical. But they are worth remembering.

Sometimes people talk about the danger that a quarantine will deeply impact trade. This is a real issue. But it’s good to be able compare this cost with what has happened before in vulnerable communities. The memory of the difficulties faced in American Samoa were not remembered for generations. The deaths of 1918 were remembered in Western Samoa, as was the name of the ship that brought the virus. Globalization has changed the world’s economies profoundly since 1918, particularly given the key role of air travel. And yet most societies could withstand short disruptions of trade if necessary.

I should say that I am not a scientist or an epidemiologist, but a social scientist and historian who mainly focuses on the politics and policy around infectious diseases (HIV, avian influenza and Zika). My point is that not that quarantine is always called for, that policy should be made based on the worst-case scenarios, or that quarantine could work equally well in all places. But the choices faced by small island states in the Pacific or the Caribbean may be very different from those faced by Canada or Germany. And even within nations, do remote and vulnerable communities implement quarantine, and if so, when?

There is still much that we don’t know about this outbreak. History suggests, though, that in some circumstances, and when the threat is great enough, quarantine may be useful tool. The difficult question is to judge whether and where that may be the case with this outbreak. How do we balance economic interests, international health regulations and human rights with the need to protect peoples’ lives, when so much is still unknown? How long should quarantines last and how complete should they be? And there is one more question that the 1918 experience raises. How should the communities that will bear the costs and risks of the decision to implement (or not) a quarantine be consulted? In 1918 in Western Samoa local peoples had no effective way to make their voice heard. It’s important that the voices making decisions not only be academics and government authorities, but also the people in different communities and nations that will be impacted one way or another.

I spend way too much time on Twitter, much of which is a waste of time, such as when I pop up in Twitter threads that are promoting conspiracy theories. I always say that this outbreak was not caused by a bioweapon created in Wuhan, and that Bill Gates is not responsible. I also argue that when people are frightened they search for meaning, which feeds conspiracy theories. And that these same conspiracy theories can be dangerous, because peoples’ behavior is shaped by what they believe. Why would you put on insect repellent or install window screens if you think that Zika is caused by Monsanto polluting the groundwater? I don’t think that my efforts or tweets are limiting the spread of conspiracy theories around the novel coronavirus. But I do listen to a lot of voices about this outbreak.

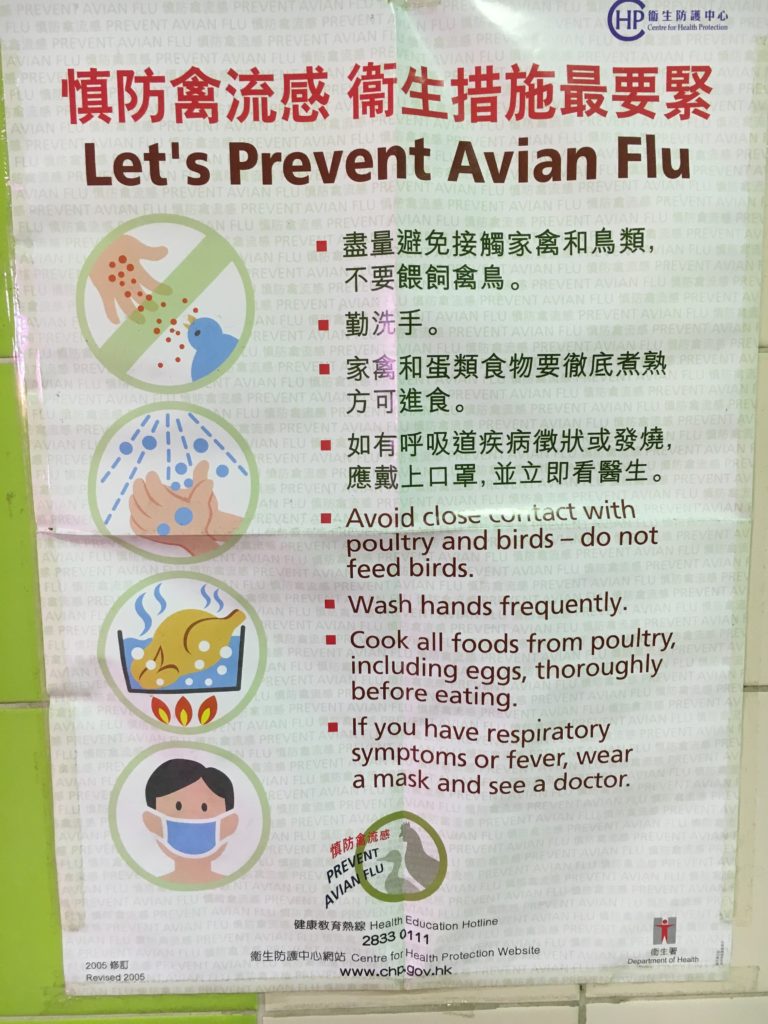

One point that I hear on Twitter is that people are over-reacting and that influenza kills far more people every year than this outbreak has. I’ve published three articles related to influenza, covering everything from viral sample sharing in Indonesia to the problems posed by wet markets in Hong Kong. We don’t yet know how serious this pandemic will be. Currently, information on this virus becomes outdated in the space of days, or sometimes hours. But the mortality rate currently for novel coronavirus seems to be around two percent. This number may go down drastically (we hope) if it proves that many people have mild cases of the disease. But if you do the math, there is no comparison between that figure and the death rate in a typical flu year. Perhaps 60,000 people die in a bad flu year in the United States, which has a population of 326 million. There is reason to treat this outbreak differently. I hope that this pandemic (yes, it’s a pandemic, even though the WHO hasn’t yet declared it to be one) will prove to be like H1N1, when there was immense fear, but the final death rate proved to be similar to a regular flu year. But we don’t know that yet, and there’s good reason to plan and prepare now while there is time. Part of that consideration should include a discussion of the pros and cons of quarantine and other social isolation measures.

Lastly, it’s also important to note that quarantines can impose great costs if done badly, and perhaps even promote the spread of the virus. It may be that hundreds of thousands of people fled Wuhan before the quarantine went into effect, which may have helped to move the virus to neighboring states. It also created tensions as people in those neighboring states feared the incomers. The extent to which the quarantine in China has worked is still unknown; let us hope that it proves successful, just as Poyer’s was long ago in American Samoa. But the dangers and costs of a badly designed quarantine that does not take into account human rights and local needs is also worth considering.

References:

Tomkins, S. (1992). The influenza epidemic of 1918–19 in Western Samoa. The Journal of Pacific History., 27(2), 181-197.