Britain’s vaccine success in the midst of a pandemic

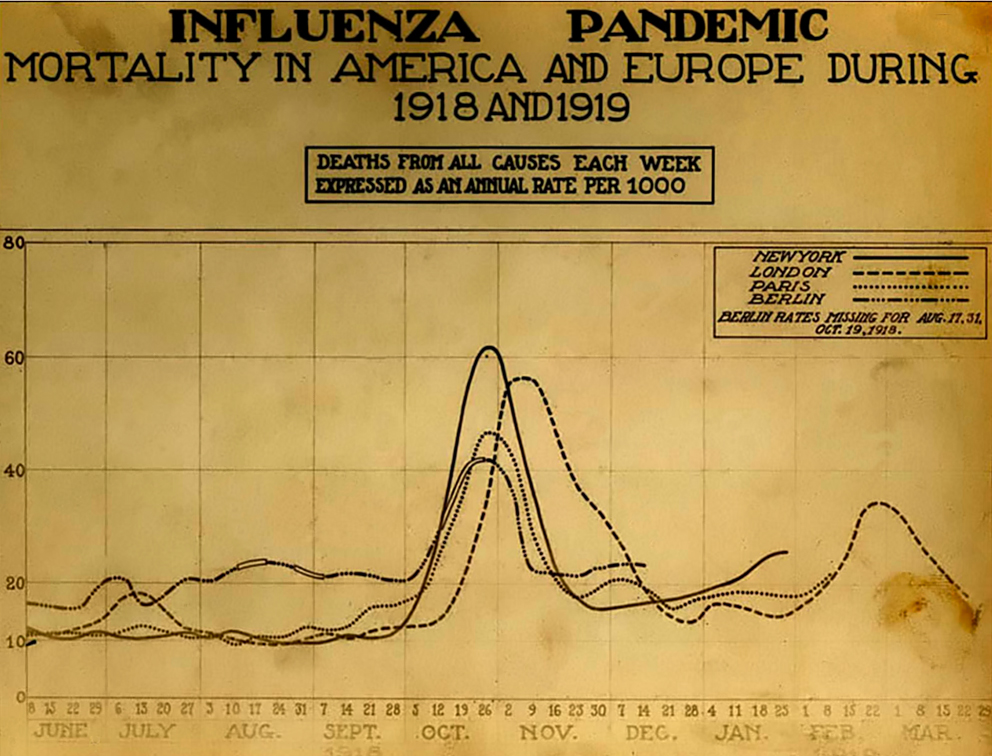

The early story of Britain’s reaction to COVID-19 was an unmitigated disaster, driven in part by uniformed cabinet discussions of herd immunity. Even Prime Minister Boris Johnston himself was infected with COVID-19. As if this story was not difficult enough, a new variant of COVID-19 appeared in Essex towards the end of 2020. We now know that not only is this variant more communicable, but also may be more deadly. In late December this virus came to dominate all the COVID-19 clades in Britain, and caused a remarkable surge in infections.

In spite of this difficult history, Britain has pulled of two remarkable achievements. First, it has conducted outstanding genomic surveillance. While Denmark was also doing so, it was the British tracking which revealed the extent of the threat these new variants posed. Now other nations, such as the United States, are playing catch-up, as they try to create an effective system for genomic surveillance. Even more remarkable, Britain has joined a short list of nations (along with Israel and the United Arab Emirates) leading the global race to vaccinate their populations. How was this success achieved?

Paul Waldie has a remarkable article in Canada’s Globe and Mail, titled “How Britain became a world leader in COVID-19 vaccine distribution – despite other pandemic problems.” In Waldie’s narrative one remarkable woman, Kate Bingham, and the task force that she led, managed to identify the likely winners in the vaccine race, negotiate contracts, and bring vaccine production home to Britain. What is most impressive is how proactive the task force was. Britain has had many missteps and still faces many challenges. Yet when the history of this pandemic is written, I think that -based on Waldie’s description- this task forces’ actions will be held up as a case-study of effective leadership during a crisis.

Shawn Smallman