The power of smartphones in online teaching

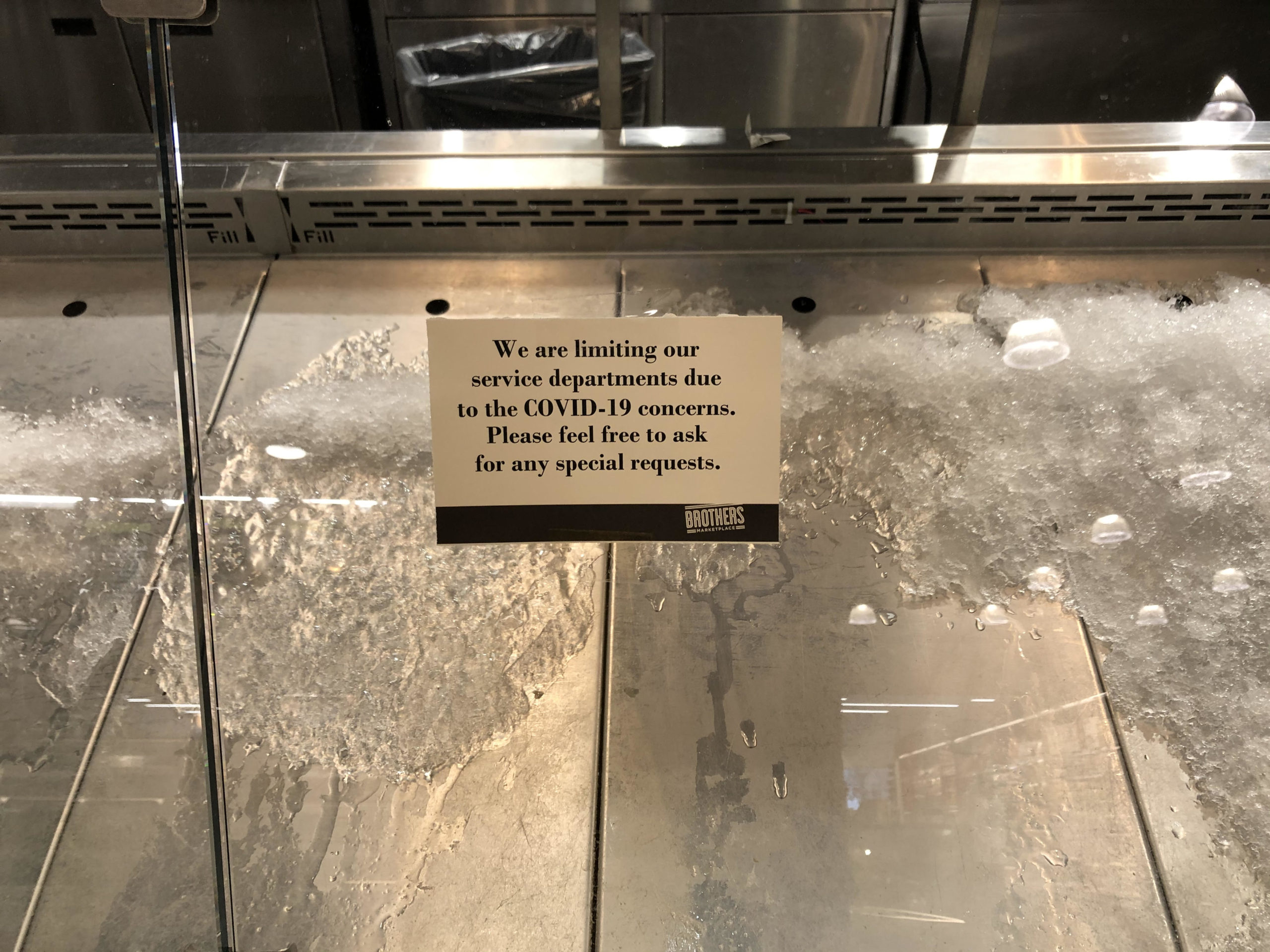

One of the great lessons in life is the power of radical simplification. Everyone who has traveled has had the experience of realizing that even the most basic statements and vocabulary can allow you to exchange key information. Right now, many people are radically simplifying their lives in self-quarantine, whether it be having a family member cut their hair, or using an old sewing machine to make face masks. The number of people rediscovering the value of even a small garden reminds me of England during World War Two. Our grandparents and great-grandparents already did this.

So it’s interesting to learn that the same trend is happening in online education, where people are interested in how to use phones as a learning tool. The idea alone might make some of my senior colleagues’ heads’ spin around much like Linda Blair’s in the 1973 American horror film “the Exorcist.” They believe that phones are responsible for the decline of civilization and culture, much as Plato and Socrates once argued that the invention of writing had destroyed memory skills and damaged learning. Nonetheless, in some developing nations smart phones are playing a key role in permitting online learning during the COVID-19. I recommend this article by Anya Kamenentz in NPR on “How Cellphones Can Keep People Learning Around The World.” It turns out that phones may also be an appropriate technology in many educational contexts. …