Ethiopia, Innovation and COVID-19

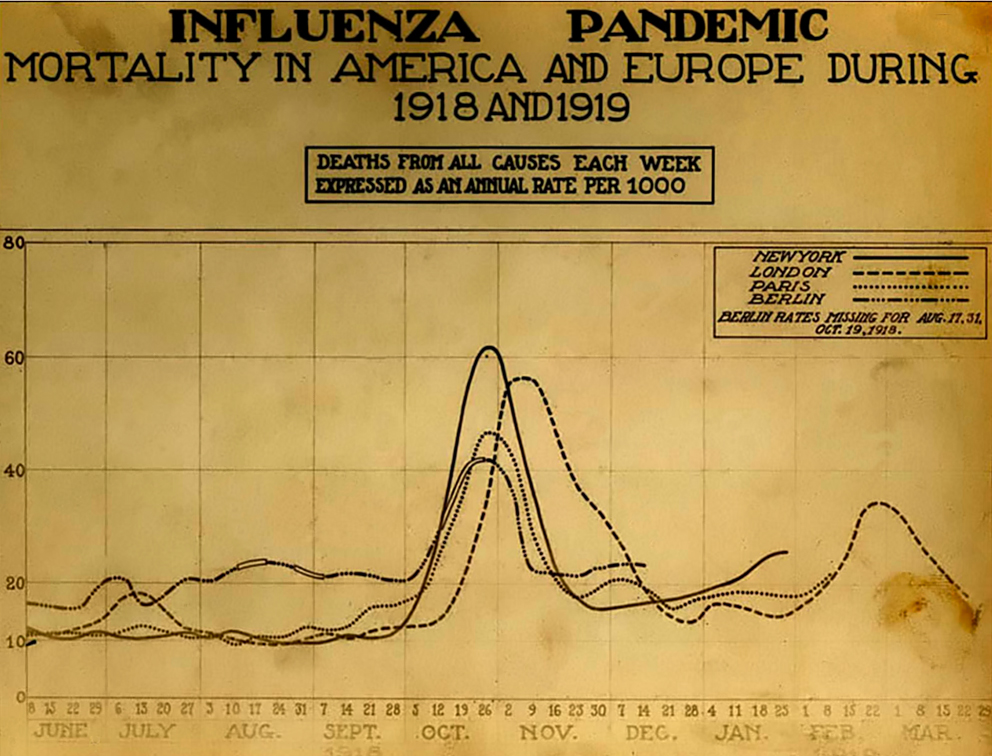

One of the realizations that has come with COVID-19 is that the old binary between developed and developing countries is deeply flawed. Some nations that are less wealthy (Vietnam, Thailand) have succeeded very well in limiting the virus’s spread (at least in June 2020), while some wealthier countries (the United States and Great Britain saw their governments fail to control the outbreak, despite not only their relative wealth, but also sophisticated health care systems.

In the United States the CDC and FDA decided not to adopt a test for COVID-19 that was recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). But their effort to create their own test was badly flawed. When that test proved not to work, it set the US testing back perhaps a month or more behind other nations at the most critical moment in the virus’s spread within the United States. In contrast, countries that adopted the WHO’s recommended test were able to test their populations at scale.

In Boston, there was a testing debacle after a number of people were infected at a Biogen conference. Even after people reported symptoms and repeatedly sought testing they were unable to be tested, because they did not meet the overly strict criteria that included travel to China, or contact with someone from China. The result was a disaster, which saw the outbreak flare so that Boston had one of the worst outbreaks in the world. Meanwhile, Vietnam carried out a very thorough testing program that has allowed to control the outbreak to this date.

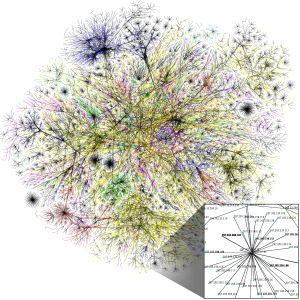

One of the most interesting points for me has been the relative difference in innovation between some developing countries and the United States, which is the home of Silicon Valley. In the U.S. there is still no national contact tracing app. Instead individual states (such as North and South Dakota) have had develop their own. But at a national level, the rate of innovation has been painfully slow. In contrast, some developing countries have moved with amazing speed. One of the success stories has been Ethiopia. As Simon Marks described in an article on the Voice of America website, Ethiopian developers quickly created seven different apps to help with everything from contact tracing to supporting health care workers. What is clear is that the size of nation’s economy does not necessarily correspond to its ability to innovate and adapt. American exceptionalism aside, wealthy nations must overcome the hubris and sense of exceptionalism, which have hampered their response to the pandemic. When developed nations take an interest in the the innovations in places from Ethiopia to Thailand, their own response will improve.

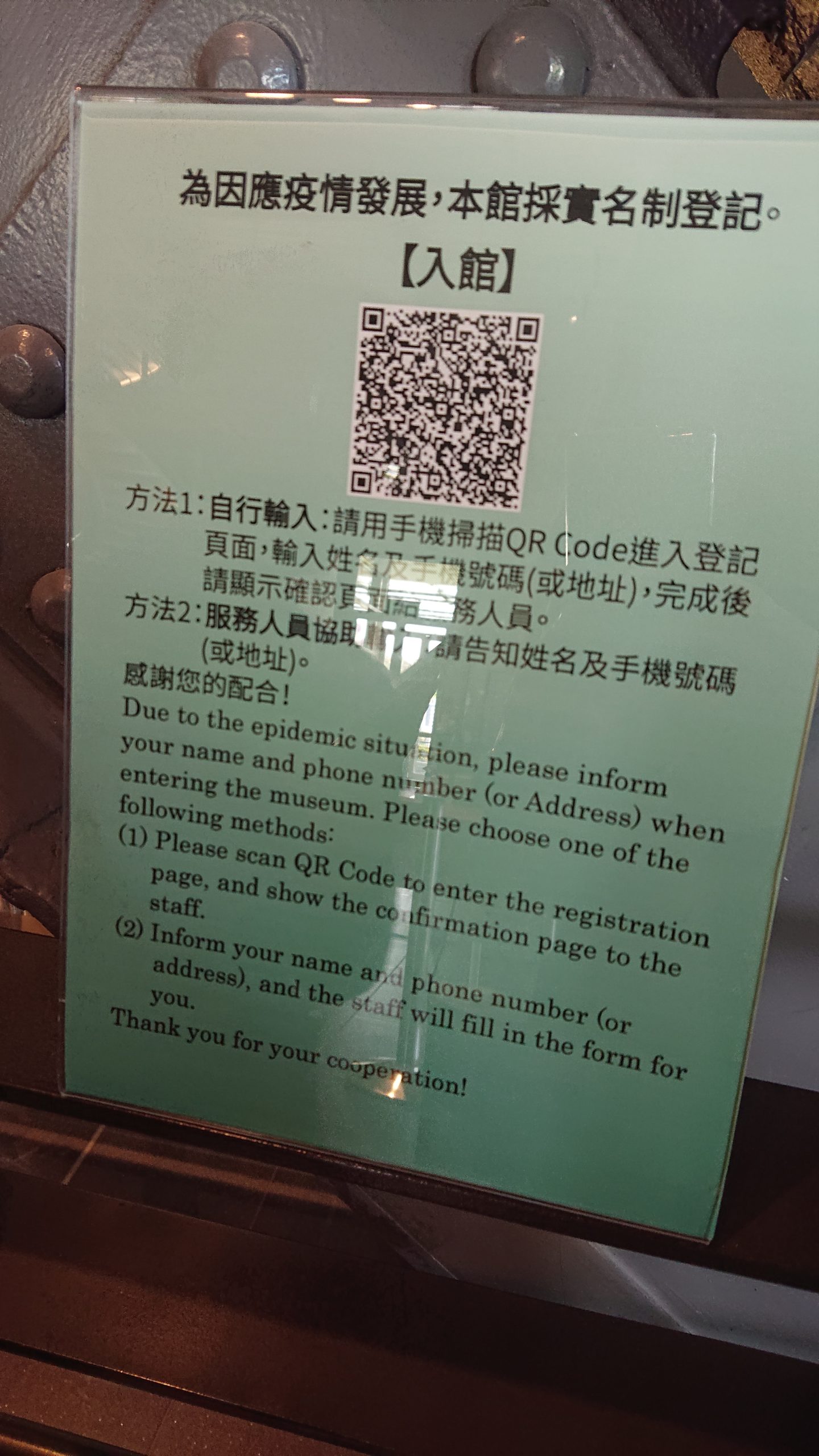

A few years ago, I was in Hong Kong, Macau and Shenzhen. When I asked at a coffee shop in Hong Kong if I could pay with a credit card, the clerk said that they could do that. Would I mind waiting while they took the machine out from the cupboard? It would take just a minute to find the keys to the cupboard. At this point, I was embarrassed and ask them not to. But they wanted to help me, and insisted on hooking up the credit card machine for the foreigner. But credit cards felt antiquated in a world in people used WeChat to pay for their subway cards, get their groceries, and order deliveries. People never had touch a device to put in a PIN. When I came back, I realized how antiquated our entire payment architecture is. I think about this during the pandemic every time I go to a gas station or department store and have to first swipe a card, and then put in my PIN on a grungy pad. Of course this is the tip of the iceberg. Why do I still need to pay bills with a check in an age of Venmo and Paypal? In Australia checks have nearly disappeared as a payment form, and it has been more than a decade since most people used one. Five years ago I was talking with an Australian. She said that she was stunned when she moved to the U.S. and people still wanted checks. And why do forms in the US still ask for my department’s fax number?

In Shenzhen I saw the sophisticated drones, electronic devices, and pristine infrastructure. Afterwards when I traveled to New York and saw the state of the airport, it felt like traveling twenty years back in time. In the United States, there is a sense of exceptionalism, which equates modernity and power with being American. But from Asia to Africa there are innovations, technologies and approaches that Western nations -particularly the United States and Britain- would benefit from adopting, particularly during this pandemic. It’s not that the developed/developing binary doesn’t isn’t useful in some circumstances. But in some respects it can conceal more than it reveals.